As a child, my visits to India were shepherded by the dreaded “what do you want to be when you want to grow up” question. My choice; “lawyer”. And swift came the response, “do something respectable”. Years later, even as India jumps through Moody’s ratings and Ease of Doing Business rankings, its disdain for the judiciary is unchanged. And, unless India fixes this pivotal problem, development is illusory.

Sri Sri Ravi Shankar can perhaps brush it aside with a session of deep meditation, but, for the country, the NGT’s actions are symbolic of a larger issue and a slippery slope that it cannot afford to go down on.

Less than seven years ago, a former minister made a stunning accusation – eight former Chief Justices of India were corrupt. More recently, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI)’s pursuit of a hawala operator eventually led them to a retired judge of the Odisha High Court, resulting in the current allegations of corruption against the highest echelons of the judiciary. Add to it the recent television expose of a cash-for-judgment scam, which showcased the link between court and bribery. The alarming “lack” of furor over these stories reflects how little India’s citizenry expects from its judicial system. And that lack of expectation is any judicial system’s single biggest failure.

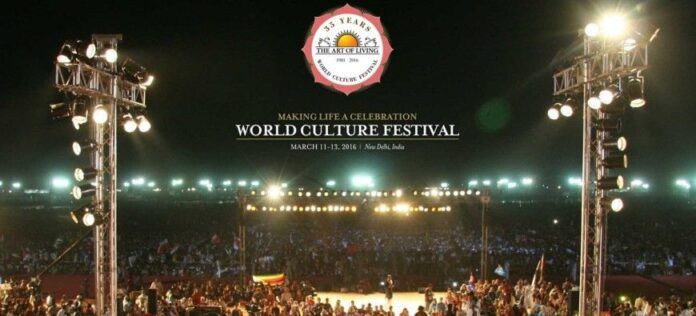

A key example of just what’s wrong with the system is the high profile case involving the Art of Living and the National Green Tribunal (NGT) over purported damage to the Yamuna’s floodplains. This particular case, a test case for an area of law that is in its global infancy – environment legislation, caught my attention from the onset.

Now, the NGT comes with an interesting resume. Take the case of the mining row in Meghalaya, where the Tribunal banned the transport of already extracted coal without investigating the legality of the extraction. Or the case of the Mantri Tech Zone, a construction project that was sanctioned after compliance with a 30-meter zoning requirement. After construction commenced, however, the NGT arbitrarily increased the buffer zone to 75 meters, leading to a long drawn out dispute. The agency’s penchant for after-the-fact decision making is interesting, to say the least.

In the Yamuna floodplain case, the NGT set up an expert committee to assess the impact of the Art of Living’s World Culture Festival (WCF) on the floodplains. The committee, defying all expectations of a long-winded process, promptly proposed a fine of INR 120 crore. And, in an equally quick volte-face, the committee’s chairperson then proceeded to discard the fine and termed its own findings unscientific! The NGT, however, chose to keep this follow-up communication under wraps.

In the meantime, the Art of Living faced widespread backlash and a media trial that publicized the INR 120 Crore fine. Neither did the NGT publicize its own finding that the fine was baseless, nor did it issue any relief when members of the committee publicly reprimanded the defendant even before commencing investigation. In fact, one member – Prof C R Babu – went so far as to give an arguably defamatory interview to a magazine. That no one seemed to question the alacrity with which a judicial body intentionally engaged in a self-deprecating publicity stunt was a stunning revelation in itself.

Unfortunately for the Art of Living, its single biggest failure was its inability to read the bench’s bias from the beginning. For example, NGT chairperson Justice Swatanter Kumar and his team declined the Art of Living’s initial offer to pay a compensation of INR 5 Crores through a bank guarantee, a globally accepted and preferred monetary instrument. Substantive grounds for denial? None.

In another slight, even as the organization submitted a challenge to verify the contents of the NGT’s assessment report, the NGT instructed the expert committee to plan action on that very report! In what can only be termed as a mockery of due process, the NGT had (by way of analogy) ordered that the suspect be hung even as the police was investigating who had committed the crime. Was someone at the NGT determined to find the Art of Living guilty?

Midway through the hearing, the NGT then insisted on a new committee to re-assess the event site, overruling objections from the organization. However, when this new committee failed to identify any substantive damage caused by the WCF, the NGT (incredulously!) chose to ignore the committee’s submission.

If this is how the NGT conducts its matters, it comes as no surprise that many of its (particularly Justice Kumar’s) decisions have been overturned by the Supreme Court; the latest being the admonition for interfering with appointments to state pollution control boards.

The writing is on the wall. Justice Kumar and the NGT are determined to prove that the Art of Living is guilty of reasons that they know best, and neither fact-finding nor the requirement of a fair trial can change that. What is even more revealing, however, is India’s, and the Art of Living’s, willingness to put up with such absurdity. Clearly, the Art of Living missed out on the “art of dealing” course. Perhaps, it should have moved the Supreme Court when it could have. Instead, it now finds itself straddled in a volleying match with a pre-determined outcome.

Nothing can be more alarming for a country than when its judicial bodies determine a verdict before adjudication. Sri Sri Ravi Shankar can perhaps brush it aside with a session of deep meditation, but, for the country, the NGT’s actions are symbolic of a larger issue and a slippery slope that it cannot afford to go down on.

Note:

1. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of PGurus.

- Changing Political Winds – PK’s Youth Factor - March 13, 2019

- India’s Slippery Slope of Fair Trials – AoL and NGT - December 6, 2017

In this democracy judges cannot be judged. People’s faith in Judiciary is lost many a time. NGT a money making Tribunal which is an open secret stooped to low levels.

The real problem in India is there are judges who are selected from the coterie of Bar Association of whom Kapil Sibal, Chidamabaram, Dave, Prashant Bhushan, Kamini Jaiswal, Mehmood Paracha are members. There is hardly any quality left.

In case of Ram Janma Bhumi our courts take 50 years to hear the case & still people are waiting for the judgment. Hindus are real tolerant people. In other societies such delays would have seen larger ramifications.