One of the prime reasons for this sorry state of affairs is that there is no “strategy” at the national level for the indigenization of defence production

Background

Since independence, some 70 years ago, defence production has largely remained in the hands of the public sector – in the form of Defence PSUs and Ordnance factories. The share of the private sector has been minimal. This has largely been the reason for India’s defence inventory still being predominantly imported.

Even the so-called “indigenized” inventory held with all the three Services has a significant percentage of imported content. If we go down to the component level in critical items like weapons and sensors, the picture is still starker. And if we take into account the material content for strategic characteristics like stealth etc., the situation is dismal.

The word ‘military’ pertains to the Armed Forces and includes men, material and morale, of all the three services, Army, Navy and Air Force.

One of the prime reasons for this sorry state of affairs is that there is no “strategy” at the national level for the indigenization of defence production. Indeed there is not even a commonly accepted definition of the term “indigenization” much less a common understanding of how to go about it.

The primary reason for this is the communication gap which exists amongst the Four Pillars of the defence establishment in India – the Users or the Armed Forces, the Designers, in the current scenario, primarily the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), the Defence Industry, predominantly consisting of the Defence PSUs and Ordnance Factories, and last but not least Academia, which needs to produce the human capital with educational and vocational competence, with the necessary skills at functional, supervisory and managerial levels.

Figure 1:

This figure 1 shows the current conventional institutions engaged in the Indian defence establishment. The private sector, where it is engaged in any of the three domains other than the Armed Forces, needs to be interpolated into the design, make and teach functions, to a greater degree.

An even more critical reason, unaccepted at the highest decision-making levels, is that in our current system for strategy formulation in the defence domain is restricted to the political and bureaucratic elements, there is limited knowledge, as well as continuity of such knowledge where it does exist, of all the three components of what is being discussed in this article – indigenization, defence and production.

To begin at the beginning

In the public image, ‘defence’ and ‘military’ are synonymous. As can be well argued, this is not so. The word ‘military’ pertains to the Armed Forces and includes men, material and morale, of all the three services, Army, Navy and Air Force.

On the other hand, the word ‘defence’ is an omnibus word and includes amongst its many components one of the ‘tasks’ assigned to the military. In this connotation, it includes not only the whole gamut of all forces engaged in the defence of the country, but also the complete range of not merely the weapon systems and ordnance required to wage war, but also the wherewithal to support the military and paramilitary establishment.

‘Skill’ is taken to mean functional ability at lower levels of production as in welding, machining, carpentry, electrical wiring etc.

Indigenization is a term that is used in a variety of ways depending on the context. It is the fact of making something more native; the transformation of some service, idea, etc. to suit a local culture.

In the defence context, it has been taken to mean import substitution of components of defence equipment at one end of the spectrum and the manufacture of a complete weapon platform at the other.

It is also not clear at the strategic level, as to whether we are referring to the ‘indigenization’ of every nut, bolt and washer of every component of every system of every weapon platform.

When we come to the term “production”, the confusion is verily confounded. Where does production start, and where does it end? Does it include the design stage and extend to the delivery-acceptance trials stage? Or does it go beyond to the Product Life Cycle, for example to upgrades and modernizations?

Also, thanks to the prevalent system of the majority of defence ‘production’ being the responsibility of the Ministry of Defence, either through its Public Sector Undertakings or Ordnance Factories, the complex procedures, and the myriad agencies engaged in implementing these procedures, operating virtually in silos, we are surely missing the woods for the trees by concentrating our focus on issues such as Defence Procurement Procedures, Offset clauses, limits on Foreign Direct Investments, regulatory mechanisms et al.

Strategy for Indigenization

A strategy for indigenization must therefore stem from a holistic appreciation of the need gap which exists between what the troops on the ground – or in the air or at sea – require, and what they actually get from ‘indigenous’ sources, and more importantly the quality, cost and timeframe in which they get them .

Since indigenization and production are inseparable, we need to go back to the Three ‘M’s of production viz Manpower, Materials, and Money, and evolve a policy for an effective and synergistic contribution of all these factors for successful and meaningful indigenization of defence production.

Currently, these issues are not being looked at, at the strategic level, and are being addressed piecemeal by various sectors and without cross exchange of data and information.

Skill development

Addressing the ‘manpower’ issue first, let us take a look at the critical issue of skill development. As a generalisation, ‘skill’ is taken to mean functional ability at lower levels of production as in welding, machining, carpentry, electrical wiring etc.

Skills at supervisory and managerial levels are developed, if at all, in a haphazard manner, and by in-house institutions, often overridden by shop floor pressures to meet production targets.

Skills at the higher levels as in design, development, project management etc., are presumed to have been acquired at the academic institutions.

Thanks to the Prime Minister’s ‘Make in India’ programme, and the thrust on Skill development as evidenced by the creation of a separate Ministry for Skill Development, a certain degree of clarity has indeed emerged in this area.

However, strangely enough, while as many as 17 Sector Skill Development Councils have been set up, covering sectors as varied as Agriculture, Beauty and Wellness, Media, and even the Security sector (incidentally this covers security guards), there is no mention of the Defence sector.

Also while the NSDC website outlines the ministries with which it coordinates, the Ministry of Defence is conspicuous by its absence.

The cost factor is critically applicable to a weapon platform, equally in its totality or right down to its myriad minor components.

Material aspects

Taking a leaf out of the warship building industry, let us consider as mundane an activity as of manufacturing of pipes. Pipes on board a warship, numbering tens of thousands, come in various shapes, sizes, fitted out with different types of flanges, and are made of various materials, requiring various types of coating, finishing, annealing, tempering etc.

While pipe manufacture is the responsibility of the shipyard, one can imagine the complexity of the myriad other components which make up the equipment, subsystems, and subsystems of a modern weapon platform, be it an Armoured Fighting Vehicle, Light Combat Aircraft or Submarine. This equally applies to flanges and hoses, and many other components which go to make up a modern weapon platform.

When we move onto the strategic material requirements such as for EMI compliance, stealth, noise reduction etc. we are convinced that the need for acquisition and development of strategic materials cannot be left to individual manufacturing organizations, in isolated domains of the defence sector, but can be met only by an equally strategic and holistic approach.

Technology – the real issue

Extensive attention is paid at the strategic level to various aspects such as international relations, threat perceptions, intelligence, internal security, counterintelligence, cyber issues, nuclear issues, budgets etc. Many of these, in fact, have a technology dimension.

Similarly, defence, production and indigenization cannot be successful if technology, its acquisition, development and deployment are not addressed from a strategic viewpoint.

Thus, the start point of indigenization of defence production really lies in evolving a strategic policy for technology acquisition. By this, it is meant that in addition to looking at a strategy for weapon platform acquisition, we need to look at a strategy for technology acquisition if we are to seriously address the indigenisation of defence production.

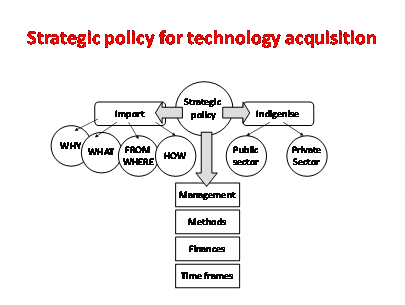

Figure 2:

Figure 2 is a suggested schematic for strategic policy formulation for technology acquisition to address indigenization of defence production effectively. Obviously, we need to include all the stakeholders, particularly the Four Pillars in the policy formulation process. This policy needs to be deployed as suggested in the figure 3 below.

Figure 3:

The cost factor

The cost factor is critically applicable to a weapon platform, equally in its totality or right down to its myriad minor components. Unfortunately, our defence strategists are not financial experts and the reverse is not true either. So we get bogged down to the ambiguity in the various clauses of the Defence Procurement Procedures and the inability to reap the benefit out of the Offset clauses.

The questions to be posed strategically are not of the ‘price’ but of the ‘cost’. What for example is the opportunity cost, as in the benefits which the country would derive out of indigenising a particular component or material? Or the cost of denial, if a specific system or technology or material was denied to us due to political reasons?

What is the cost of IP involved in the Transfer Of Technology (TOT) of a specific item? What is the cost of Human Resource needed to imbibe the TOT even when it is offered? While we are perhaps one of the largest importers of military hardware in the world, can we honestly say that we have a system or templates to work out the costs of all these factors?

More importantly, has been brought out in various reports available in the public domain, what is the cost of an item not being available to the Armed Forces in the time frame that it has been promised by those responsible for the indigenous development, be it the DRDO, or the Defence PSUs or the Ordnance Factories?

A strategic approach to solve this apparently “insolvable conundrum is contained in Part II of this paper.

To be continued…

[…] 1 of this series can be ‘accessed ‘ here. This is Part […]