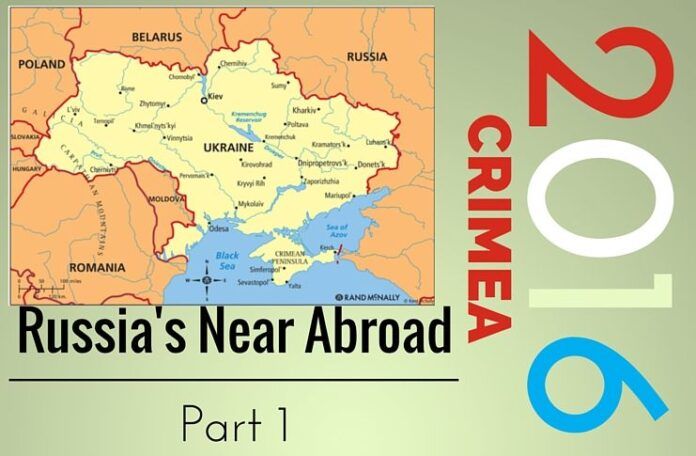

[dropcap color=”#008040″ boxed=”yes” boxed_radius=”8px” class=”” id=””]T[/dropcap]here are several reasons for revisiting this dynamic region. The powers that be were preparing for a World War III in 2016 and the final piece in the jigsaw puzzle was the appointment of an American president who would make the decision, his. Unfortunately, the elections show that the leader of the Republican Party is not likely to back this scheme; he wants to befriend Putin, not declare war against Russia. Perhaps the plan may come to fruition if the “female card” gains access to the White House. Either way, Crimea has now become “part” of Russia.

Secondly, the method of Russian annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol has alerted other countries that could suffer a similar fate, and their safety is in Article 5 of NATO, which states that an attack on one country is an attack on all NATO members. Most of the smaller countries that lie in Russia’s “sphere of influence” want to join the EU and NATO. Russia naturally objects to NATO operating on its borders.

The third reason for revisiting the Near Abroad is that within a year there could be dramatic economic changes. One source showed that Turkmenistan’s GDP in 2014 was $48 billion; in the following year the figure was $90.5 b, almost double. A pipeline may have been completed and the sale of oil or gas could explain this dramatic rise. All countries in this part of Russia’s Near Abroad are showing signs of tremendous improvement, though for different reasons.

[dropcap color=”#008040″ boxed=”yes” boxed_radius=”8px” class=”” id=””]T[/dropcap]he focal point of insecurity in Europe and Central Asia is Russia’s annexation of Crimea, which was declared independent on March 17, 2014.1 From Russia’s point of view, Crimea had been Russian since time immemorial. Most Crimean residents are Russians and a quarter of the population are ethnic Russian. In 1954, Nikita Khrushchev made Crimea a part of Ukraine for administrative reasons, as a dam was going to be built on R. Dnieper to serve the whole agricultural area. Even moderate Gorbachev ascertained that Crimea was Russian. Ukraine’s argument was that when it became independent, Crimea was part of it and should remain so. The truth was that “Uncle Joe,” Stalin shuffled populations by force to such an extent that the Tartars, the rightful owners, were relegated to a minority group. They remain at 12% of the Crimean population. Secretary of State John Kerry knows that Crimea gives Russians unhampered control of the Black Sea and access to the Mediterranean; his view is therefore Russia’s annexation of Crimea was “an act of aggression.” In support, German Chancellor Angela Merkel insisted that sanctions would stay on Russia until Crimea was part of Ukraine again.

The Crimean debacle is a history of tragedies. Russia and Ukraine treat Tartars as second class citizens. Russia has no right to back its expat citizens in Eastern Ukraine from claiming Ukrainian territory. Ukrainian President Poroshenko did not have the vision to realize that his country that could not pay its energy bills could challenge a military power and neighbour to a world war. Poroshenko stands to lose two provinces, Donbass and Luhansk, which are claiming autonomy. No major power has a right to levy sanctions on its own or through an alliance: the ones that stand to lose most are the poor, which goes against UN efforts to raise the standards of the masses.

Crimea, according to some, is part of Ukraine, which in turn is part of Russia’s Near Abroad. From Russian Defense Minister Sergey Shoygu’s statements, at the 2016 Moscow conference on international security, we conclude that Russia treats the Near Abroad as domestic policy while Syria falls into a foreign policy category.2 This implies that Russia can do what it likes with its domestic policies. The West, naturally takes a different view: the countries within Russia’s Near Abroad have a right to forge their own destiny and many of them want to be pro-West, as members of the EU and NATO. From a strategic point of view, Russia objects to Western influences, especially military, in its Near Abroad. These divergent viewpoints account for most of the instability in the region.

This is not the first time that Russia wanted to slice an established state. After the 2008 Russia-Georgia war, Abkhazia and South Ossetia declared independence from Georgia. To a certain extent this division was justified since “Uncle Joe,” Stalin was a Georgian who was responsible for massive ethnic cleansing during his rule. Abkhazia is mainly Muslim, and with Russian cooperation, wants to be the home of those Muslims who have been displaced. South Ossetia is linguistically linked with Persia and wants to be a part of North Ossetia, which is more industrially developed and pro-Russian. Russia’s protection of Abkhazia has led to many Georgians fleeing the country and seeking umbrage in Georgia.

References

-

Stefan Kirchner, “Crimea’s declaration of independence and the subsequent annexation by Russia under international law,” Journal of International Law, January 9, 2015.

-

“Russian Defense Minister names Russia’s main task,” pravda.ru, April 24, 2016.

To be continued…

- Part2 – China’s Road to Superpower status - July 20, 2017

- Part1 – China’s Road to Superpower status - July 18, 2017

- P2 – Can or should Qatar be ostracised? - June 29, 2017

It is not “annexation” – its accession.