The recent ruling echoes many of Justice Malhotra’s opinions. It says that the larger Bench would have to examine the “interplay” between the freedoms provided under these Articles.

There are two interesting aspects to the Supreme Court ruling on the Sabarimala issue. The first is that it is ‘forward-looking’ and the second is that it reflects a significant extent of minority ruling of one of the judges in 2018 when it ruled in favour of entry of women of all ages to the sacred shrine.

The court in its verdict on November 14, referred a petition seeking review of its 2018 judgement to a larger seven-judge Bench. In doing so, the majority verdict of 3:2 said that it had to keep in mind the larger matter of the “powers of constitutional courts to tread on the question as to whether a particular practice is essential to religion or is an integral part of the religion…” It gave the example of other traditions, such as female genital mutilation in the Dawoodi Bohra community, and added that issues arising out of such cases “may be overlapping and covered by the judgement under review”. It also gave instances of the prohibition of entry to women in places of worship such as mosques, and the bar on entry to non-Parsis into the Fire Temple.

The court has referred the issue of deciding on accepting the review petition to a seven-member Bench, but has not stayed its 2018 ruling. For now, therefore, women of all age groups can enter the Sabarimala shrine of Lord Ayyappa.

In other words, the apex court took the position that any verdict on the Sabarimala issue should bear in mind its repercussions on the faith and practices of other religions as well. This forward-looking approach is unusual since the court normally decides on the case in hand. While it is common for courts to club similar petitions, it is rare for the judges to take into account cases that are not listed before it. The majority opinion has clearly held the view that it is best to anticipate precedents that can be set out of a final verdict on Sabarimala.

There is nothing wrong in taking a holistic position because once the Pandora’s Box is opened, it could lead to multiple problems and litigations which the courts will have to tackle. But these would not be ordinary cases of disputes; they would constitute matters of tradition intrinsic with religion.

It is easier said than done to decide on issues of religion strictly on the basis of rights the Constitution provides. The practise of religion is also a fundamental right given to every citizen of the country. And when there is a seeming clash between the two rights, the courts have to walk a tightrope. With this in mind, the five-judge Bench has done well to look forward. Incidentally, while delivering its judgement in the Ayodhya case, the Supreme Court did take faith into account even as it considered the pieces of evidence placed by the contesting parties to lay claim on the disputed land’s title.

Now for the second interesting aspect. In her minority judgement in September 2018, Justice Indu Malhotra had pointed out that the verdict would have “far-reaching ramifications” for “all places of worship of various religions” which have their “own practices” considered “exclusionary”. She had said that the fundamental rights guaranteed under Article 25 of the Constitution to freely practise one’s faith did not get overridden by the equality doctrine provided under Article 14.

The recent ruling echoes many of Justice Malhotra’s opinions. It says that the larger Bench would have to examine the “interplay” between the freedoms provided under these Articles. Justice Malhotra had also raised the subject of constitutional morality, saying that it referred to the harmonisation of fundamental rights in order to ensure that religious rights were honoured. In its November 14 ruling, the apex court pointed out that, since constitutional morality had not been defined in the Constitution, one needs to ponder on whether it was limited to religious beliefs or encompassed the Preamble. But in doing so, the recent verdict did bring into play the issue of constitutional morality which Justice Malhotra had flagged.

Incidentally, Justice Indu Malhotra was this time part of the majority verdict, whereas two other judges who were part of the majority verdict in 2018 were in a minority on November 14.

In 2018, the majority view had said that the violation of fundamental rights implied the violation of constitutional morality. One of the Justices had then expanded on the subject in the following words: “The magnitude and sweep of constitutional morality is not confined to the provisions and literal text which the Constitution contains; rather it embraces within itself virtues of a wide magnitude such as that of ushering a pluralistic and inclusive society…”

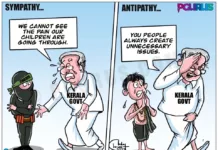

Apart from the above two observations, the takeaway from the recent judgement is rather hazy. The court has referred the issue of deciding on accepting the review petition to a seven-member Bench but has not stayed its 2018 ruling. For now, therefore, women of all age groups can enter the Sabarimala shrine of Lord Ayyappa. Whether that will happen on the ground, remains to be seen. It must be recalled that a serious law and order issue had erupted in Kerala when some women tried to enter the shrine soon after the 2018 judgement but were encountered by activists — both men and women — who opposed the entry of women of certain age groups, into the Sanctum Sanctorum. Despite being equipped with the court order, the State administration could do little to facilitate the entry of women. The situation may not be very different this time around, more so when the court has yet to give a final decision on the vexed issue.

However, since the apex court believed that the issue needed the attention of a larger Bench, it would have been more appropriate for the Justices to have stayed the earlier verdict until the matter was resolved by the larger Bench.

Note:

1. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of PGurus.

Surely a Stay Order would have been the most logical step in ensuring peace and harmony until such time the court can make a decision. Even a simple decision such as this if cannot be taken, then it only reflects on the level of the SC judges’ competence and intellectual capacity to make a decision on such a matter of national importance. Further the right to gender equality, faith and worship is still undecided and a decision to stay the proceedings to maintaining the status quo is most appropriate.