Srinivasa Ramanujan: The mathematical genius

The world we live in today has people unscrupulously trying to snatch land away from rightful owners to install a statue of their late father. The reason is that their late father was an employee on the payroll of the company that existed in that location where they wanted the statue to come up. The irony is that the land that belonged to the organization where their father worked once upon a time has changed hands, and the rightful owner today has no connections with that organization. His only sin, he had left an arch that announced the old organization’s existence intact, considering its heritage.

In this same world, we had people who felt that they had been over-compensated for the job they did. They not only came forward to return the money that they thought they didn’t deserve but also suggested ways of spending it more usefully by providing scholarships for the deserving poor and orphans.

The person who did this extraordinary deed was none other than the mathematics genius Srinivasa Ramanujan.

Coming from a very ordinary family that had no connections with mathematics, after his initial struggles, Ramanujan slowly started to blossom into a world mathematics phenomenon during his stint at the famed Cambridge University in England. Ramanujan’s one-litre stomach soon lost its battle with his one-and-a-half-kilo brain. His extremely strict vegetarianism and his attitude of caring more for mathematics than his health took its toll. Ramanujan contracted Tuberculosis, the infectious disease that affects one’s lungs, and had to be moved to a sanatorium to recover. He spent his last two years in England in sanatoriums. He was repatriated to India when he started showing signs of recovery.

As he awaited his repatriation, his alma mater, Cambridge, his host, friend, and guide at Cambridge, G H Hardy, The India office, and his parents, the Madras University decided to come together to provide all the help they could to make Ramanujan’s return and his life back in India comfortable and offer the help he would require to continue his research work.

As part of this plan, there were three things decided:

- One, provide Ramanujan employment at the Madras University in the mathematics department so that he could continue his research work there with a compensation of Rs.400 per month.

- Two, Cambridge University would provide him with a fellowship of 250 pounds per year.

- Three, Madras University would match the Cambridge fellowship with another 250 pounds per year.

This arrangement would continue for the next six years and also offer Ramanujan the opportunity to travel to England and back when he wished. They decided that this arrangement would kick off once Ramanujan came back to India (Madras).

For someone who grew up in poverty with his father, Srinivasan, slogging out at a textile shop for Rs.20 a month and his mother, Komalatammal, doing her part as part of a Bhajan group earning in one digit, infrequently, this largesse was god-sent. Anyone from that background would go on four limbs to grab such an opportunity.

But for Ramanujan, losing his hard-earned scholarship at the Government College of Arts, Kumbakonam, after failing his first term, the hardships he faced in Chennai before Sri Ramachandra Rao came into his life and offered him a meagre scholarship, the miles that he walked to tutor college students and earn a few more to sustain his existence flashed back in his mind.

This flashback made him do something extraordinary, something ordinary mortals won’t. On January 11, 1919, he decided to write a letter to Francis Dewsbury, the Registrar at Madras University, who was the executor of the three-point remuneration proposal.

Here is the reproduction of the letter excerpted from the book The Man Who Knew Infinity – A Life of the Genius Ramanujan by Robert Kanigel (Abacus, 2016).

Sir,

I beg to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of 9th December 1918 and gratefully accept the very generous help which the University offers me.

I feel, however, that after my return to India, which I expect to happen as soon as arrangements can be made, the total amount of money to which I shall be entitled will be much more than I shall require. I should hope that, after my expenses in England have been paid, £50 a year will be paid to my parents and that the surplus, after my necessary expenses are met, should be used for some educational purpose, such in particular as the reduction of school-fees for poor boys and orphans and provision of books in schools. No doubt it will be possible to make an arrangement about this after my return.

I feel very sorry that, as I have not been well, I have not been able to do so much mathematics during the last two years as before. I hope that I shall soon be able to do more and will certainly do my best to deserve the help that has been given me.

I beg to remain, Sir,

Your most obedient servant,

S. Ramanujan

Note: £1 in 1918 is approximately equal to £140 today. The fellowships that Cambridge and Madras Universities offered would total approximately Rs.74 lakh per annum in today’s value, let alone the Rs.400 per month professorship that Madras University offered.

In a world where people want to illegally grab land to install a statue of their father, here is a man who tells the authorities of the day that he has a better idea to suggest as to how they can use the excess money they are offering him as remuneration. He says he will take a small portion of what is on offer to take care of his and his parent’s needs, use some more to repay the money that the government of the day and the two universities spent on his education and upkeep, some more to fund his mathematics research, the large sum left was to be used as scholarships for the poor and orphans, and also to buy books for them. Pray, who in this world would refuse free money? This isn’t even free; it is what the government and the academia of those days thought was the worth of Ramanujan’s scholarship.

This anecdote from Ramanujan’s life only tells us one thing. Tamil Nadu has never had a dearth of good people. It is our problem that today we don’t identify and fete them; let the capable lead us and show the light.

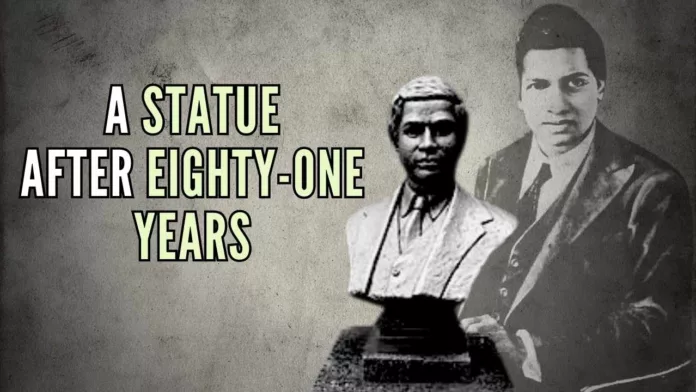

Postscript: As the title says, it took eighty-one years after Ramanujan’s death for someone to decide to cast his bust. The world of mathematics came together in 1981 to commission a Minnesota, USA-based sculptor, Paul Granlund, to make the bronze Ramanujan statues. One of the ten busts that were made found its way into a small open almirah in the hall of Ramanujan’s widow, Smt. Janaki Ammal’s home.

Note:

1. Text in Blue points to additional data on the topic.

2. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of PGurus.

For all the latest updates, download PGurus App.

- Was Ambedkar anti-Hindu? - April 14, 2024

- V. V. S. Aiyar – The ‘all-rounder’ Maharishi who gave it all for Bharat Mata - April 2, 2024

- Divine revolutionary nationalism of Neelakanta Brahmachari - March 4, 2024