If one analyses the course of events in Pakistan since its creation, it will be manifest that there is no honorable place for Hindus within that state.

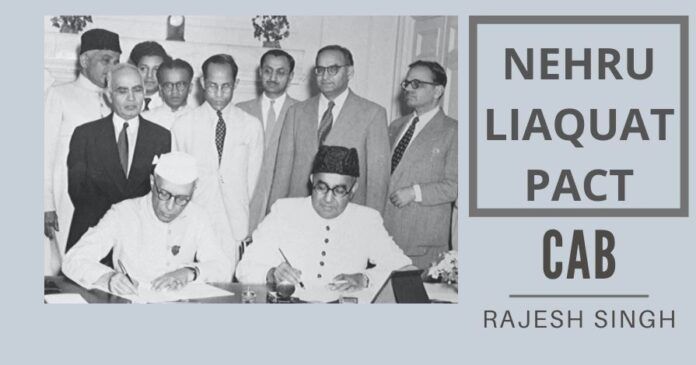

The debate on the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill 2019 brought to recollection one important development that remains embedded in history books: The Nehru-Liaquat pact of 1950. This agreement between Prime Ministers Jawaharlal Nehru and Liaquat Ali Khan of India and Pakistan respectively promised to ensure the protection of minorities in their respective countries. The agreement came in the backdrop of large-scale violence by the majority community against the minorities. Among other things, the pact decided the following:

- Refugees would be allowed to return safely to dispose of their properties.

- Women abducted and property looted would be returned.

- Minority rights would be enforced.

- Forced conversions would not be given recognition.

Why did Patel climb down from his position, despite having a gut feeling that the solution did not lie in the agreement? According to Rajmohan Gandhi’s Patel: A Life, it reflected “a conscious decision not to embarrass Nehru”.

The agreement was signed between the two leaders during the Pakistani Prime Minister’s visit to India that year. While India, in substance and spirit, honoured the pact, Pakistan did not. This was admitted to in 1966 by India’s External Minister Swaran Singh on the floor of Parliament, in response to a question by Bharatiya Jana Sangh member Niranjan Verma. Swaran Singh said that Pakistan had persistently gone against the provisions of the agreement and continued to neglect and persecute its minorities. There is no doubt, thus, that the pact was a failure.

Who is to be blamed for it? Pakistan, certainly. Had it kept its end of the promise, the persecution of minorities there would not have continued, and perhaps there would have been no need for the amendment Bill in its present form. But Nehru too allowed himself to be fooled by Liaquat Ali Khan’s fake concerns for minorities in his country. Instead of intervening directly to rescue the minorities in Pakistan — largely Hindus and Sikhs — or at least threaten some sort of reprisal — he fell in the Pakistani Premier’s trap.

Congress supporters will be quick, in their eagerness to embarrass the BJP, in pointing out that even Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel had whole-heartedly endorsed the pact. That is true, but there is more. The migration of persecuted Hindus leaving what was then East Pakistan into India far exceeded that of Muslims leaving India for Pakistan. The refugee problem had turned into a crisis, with West Bengal being choked by the inflow of people from across the border. Sardar Patel wrote to Nehru, suggesting a solution: Give an unambiguous indication to Pakistan that, if it failed to contain the migration, India would have no alternative but to send an equal number of Muslims to Pakistan. But after Nehru pointed out that this would send a wrong message to India’s Muslims and fan communal sentiments, the Sardar accepted Nehru’s reasoning. However, he was clear that something had to be done, and when the pact was signed, he, like others, was hopeful against the hope that Pakistan would abide by the provisions.

The question is: Why did Patel climb down from his position, despite having a gut feeling that the solution did not lie in the agreement? According to Rajmohan Gandhi’s Patel: A Life, it reflected “a conscious decision not to embarrass Nehru”. He could have stuck to his position — and would have found support in the party and outside too. Rajmohan Gandhi writes, “Dissatisfaction in the party and the Cabinet with Jawaharlal’s reaction to the influx had given Vallabhbhai an opportunity to strengthen himself against Nehru but he rejected it, and he rejected as well an offer of the Prime Ministership that Jawaharlal made to him at the end of February 1950.”

And yet, while he backed Nehru on the issue, he put his foot down when Liaquat Ali Khan suggested that both countries should have ministers for minority affairs. He said this response to Maulana Abul Kalam Azad’s idea that the two Bengals can create their respective ministries for minorities. Sardar Patel said: “We have conceded one Pakistan; that is more than enough.” Besides, he added, the Congress party would never accept the suggestion. It must remembered that Sardar Patel played a big role in selling the pact to the people of India and the party. He fought Nehru’s battle despite failing health, seeking to convince those who were unprepared to hear Nehru out. In a way, he kept his promise to Mahatma Gandhi not let Nehru down. As Rajmohan Gandhi notes, “For all his inhibited remarks at other times, he had been soldierly in the testing hour, protecting his colleague and keeping his last word to the Mahatma. Though he fought to win his political combats, his iron hand stopped in mid-air if the nation’s good, or a solemn promise, was threatened.”

If one analyses the course of events in Pakistan since its creation, it will be manifest that there is no honorable place for Hindus within that state.”

Patel may have been constrained, but there were others in the Nehru government who felt strongly enough to speak out against the Nehru-Liaquat accord. One of them was Syama Prasad Mookerjee. He had realized that Liaquat had come to Delhi not because he cared for the minorities in his country but because he was boxed into a corner due to the response from the Indian side of the border to the large-scale atrocities on minorities in Pakistan. Over half a million Muslims had crossed over from the Indian side to Pakistan. His plan was to somehow convince the Indian leadership to stop this migration into his country.

Mookerjee reminded Nehru of previous assurances that Pakistan had given and flouted, and suggested that a clause be included in the pact that provided for penal punishment, such as sanctions against the country which went back on its provisions. But Nehru was unreceptive since he was convinced that Pakistan’s intentions were good. In his book, The Life and Times of Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee: A complete Biography, author Tathagata Roy writes, “Dr. Mookerjee had sensed that (the suggestion to include the penal clause) would almost certainly have wrecked the impending negotiations; and if it did, Pakistan’s real intentions would be proved. But Nehru would not budge… Finally, confronted by Dr. Mookerjee in a Cabinet meeting on April 1, 1950, when he could not meet his arguments, he lost his temper and overruled Dr. Mookerjee, who had told him on his face that he was flouting all conventions of joint responsibility of the Cabinet on vital national questions, such as the one created by the situation in West Bengal.” In a letter dated April 6, 1950, Mookerjee tendered his resignation from the Cabinet. Those who continue to believe that he had acted in haste and with a view to politically enamor himself, need to absorb the following figure (which Roy quotes in his book): The government of India had admitted that, since February 27, 1950, not less than 41,89,847 Hindu had left East Pakistan.

Tathagata Roy further informs that Nehru’s Commerce Minister KC Neogy too had strong reservations about the pact. he said no East Bengali (which he was) could be expected to believe in the honesty of purpose of Pakistan. It would be an act of absurdity, he underlined.

Mookerjee’s resignation drew disappointment and dismay from Sardar Patel. The Iron Man of India, who was “distressed”, asked Mookerjee to reconsider his move but Mookerjee did not budge; nor did Neogy, who too had quit. Mookerjee’s speech in Parliament on his resignation was a masterful articulation of his decision. He said the pact was a “patchwork” given that the “evil is far deeper”. Mookerjee’s following remark during his speech turned out to be prescient: “… If one analyses the course of events in Pakistan since its creation, it will be manifest that there is no honorable place for Hindus within that state.”

Add to that list the Christians, the Buddhists, the Jains, and the Sikhs, and you have a justification for the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill.

Note:

1. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of PGurus.

The very same Congress party now is crying hoarse about CAB. They have been solely responsible for all the ills plaguing our country. The CAB is a well thought out move and should see its passage in Rajya Sabha too, Congress calls all supporting the CAB as bigots forgetting they were the ones responsible for all the sufferings of minorities in the neighbouring countries. We have 14 % population being still called minorities, scrap that status. A Uniform Civil Code would be the icing on the cake.