The focus will be on land revenue records

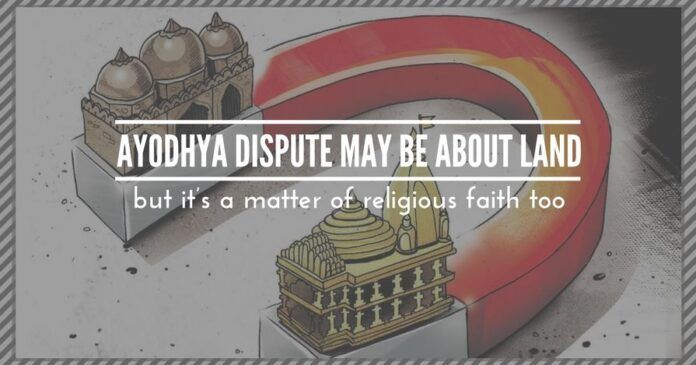

The Supreme Court recently said that it would deal with the Ayodhya dispute as a “land issue” since the case before the Bench was essentially that of a “title suit”. It indicated that the Bench was unlikely to be swayed by matters of faith when it brushed aside a Hindu organization representative’s plea that the matter concerned the faith of 100 crore Hindus. “We are not going to address these kinds of arguments”, the court curtly stated.

In the initial days, the protests were largely ignored by the mainstream media, particularly the television networks in Tamil Nadu

Technically, the apex court is right because it would be hearing a challenge to the Allahabad High Court order of 2012 which had mandated a three-way division of the disputed land, thus reinforcing the title deed aspect. Yet, it would be interesting to see how the Supreme Court manages to keep faith aside in the process, given that even the High Court verdict had factored it, and so had other earlier court pronouncements. Meenakshi Jain’s recent book, Ram & Ayodhya, offers a perspective on the issue.

On September 30, 2010, the High Court distributed the land, one-third each, to the Sunni Waqf Board, the Nirmohi Akhara and the representatives of Ram Lalla (considered a legal entity). But equally important is the argument that it offered in awarding the central dome of the disputed structure and the area in the outer courtyard to the pro-temple litigants. It said that the central dome is “being the deity of Bhagwan Ram Janmasthan and the birthplace of Lord Ram as per faith and belief of the Hindus”, belonged to the Hindu groups in the dispute. The same applied to the areas covered by the Ram Chabutara, Sita ki Rasoi and the Bhandar.

Further underlining the importance of keeping faith in mind and the insistence of the pro-temple groups that the area under the central dome had been Lord Ram’s birthplace, the High Court Bench had observed: “If this is the belief of the community… a secular judge is bound to accept that belief. It is not for him to sit in judgement on that belief.”

The court even gave some sort of constitutional validity when it said, “Once such belief gets concentrated to a particular point… it, therefore, stands on a different footing. Such an essential part of religion is constitutionally protected under Article 25.” This Article of the Constitution of India guarantees the freedom to practice and propagate religion (subject to public morality, law and order and health etc) as a Fundamental Right. In making these observations, the Allahabad High Court was obviously satisfied that the area under the central dome was the place the Hindus believed was the site of Lord Ram’s birth. The judges maintained that the central dome area had to be so considered that the “very right of worship of Hindus of play of birth of Lord Ram is not extinguished or otherwise interfered with…”. It also added that a place of “non-Islamic character” existed at the site before the construction of the mosque.

It can be argued that all of these observations and the verdict itself are now irrelevant since the Supreme Court subsequently stayed the High Court order and is now seized with hearing the pleas against that judgement. The truth is that the trifurcation of the disputed property may be under challenge, but faith remains an intrinsic part of the dispute — and not just in the case of the Hindu parties. The pro-mosque lobby is also, after all, driven by a similar motive: The demolition of the mosque had been a blow to its religious beliefs.

Interestingly, faith also occupied centre-stage when the judiciary had to contest the pro-temple lobby’s contentions

Idols of Hindu deities were installed at the site in December 1949. While hearing a case in the matter, a Civil Judge a month later granted a temporary injunction against the removal of the idols and from “interfering with the puja etc as at present carried out”. The judge also noted — something that came to be presented by the pro-temple groups in later years to bolster their claims — that “at least from 1936 onwards the Muslims have neither used the site as a mosque nor offered prayers there and that the Hindus have been performing their puja etc on the disputed site”.

The unlocking of the gates of the disputed site was done during Rajiv Gandhi’s prime ministership and continues to be criticised by the Left-Liberals even today as a game-changer for the worse. It’s important to remember what the District Judge of Faizabad said then: “It is undisputed that the premises are presently in the court’s possession and that for the last 35 years Hindus have had an unrestricted right of worship as a result of the court orders of 1950 and 1951. If the Hindus are offering prayers and worshipping the idols, though in a restricted way for the last 35 years, the heavens are not going to fall if the locks of the gate are removed.” The judge dismissed fears that opening the doors of the disputes structure would create a law and order issue: “It is clear that it is not necessary to keep the locks at the gates for the purpose of maintaining law and order or the safety of the idols. This appears to be an unnecessary irritant…”

The one important development which happened as a result of the unlocking is the formation of the Babri Masjid Action Committee (BMAC) which belligerently continued the fight against the pro-temple organisations in the court and outside. Thus, faith on both sides remained at the core of the dispute.

And, in 1993, on a petition relating to the Vishwa Hindu Adhivakta Sangh versus Union of India, the Allahabad High Court had said in response to the demand that the plea is dismissed: “When the Hindus… claim rights to have darshan and puja of that deity whom the devotee’s worship as Bhagwan and framers of the Constitution treated as a great national figure of this country and its basic culture, it is something superficial to argue that the petition is not maintainable and should be dismissed on technicalities.”

Interestingly, faith also occupied centre-stage when the judiciary had to contest the pro-temple lobby’s contentions. For instance, in the aftermath of the mosque demolition, a judge of the Allahabad High Court, SHA Raza, observed, “The genesis of the Ayodhya imbroglio lay in the belief of crores of Indian people that Lord Sri Ram Chandra Ji was born at Ayodhya. On the scale of historicity, such a faith cannot be established…”

Now, given that the Supreme Court begins hearing the matter on March 14 by keeping aside considerations of faith, notwithstanding the recent legal history of religious belief as one of the core aspects, the focus will be on land revenue records — and perhaps archaeological evidence which could complement the title deed issue.

Note:

1. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of PGurus.

It appears that the SC is going to make the dispute very simplistic and confined to the issue as a mere land dispute, ignoring the historical facts, religious practices of time immemorial origin, public order, etc. It will then boil down to a few documents and circumstantial evidences of recent origin forming the core of the case with the SC defining the contours based on their own wisdom. At this rate, one wonders what kind of justice will be rendered through the final verdict.