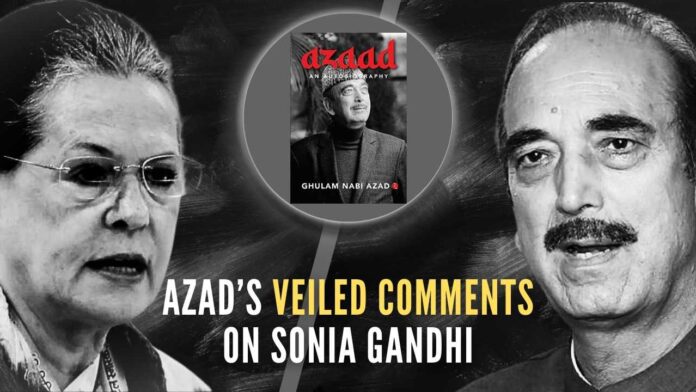

Azad’s book ‘Azaad’ out; Read the revelations about the grand old party

Senior journalists and television anchors have commented and will continue to comment till the issue is flogged well and properly, on the political revelations made by veteran politician Ghulam Nabi Azad in his recently released autobiography. Titled ‘Azaad‘ — presumably, after Azad quit the Congress and became ‘free’ — it provides an insider’s account of the challenges the grand old party faced and overcame, especially during Indira Gandhi’s and Rajiv Gandhi’s tenures as party chief and prime minister.

The thrust of the discussions in the media so far has been on Azad’s observations about the continuing decline of the party, for which he has squarely held Rahul Gandhi’s leadership responsible. Azad said in the many interviews he has given since the book’s release that as long as Sonia Gandhi remained in charge of the party’s affairs, seniors such as him were heard and consulted and that the health of the party was not as dire as it became later.

The contents of his book coupled with these interviews apparently give a positive impression of Sonia Gandhi’s leadership skills. But read between the lines, and you will notice that Azad has not really absolved her. A few instances are a case in point.

Take the much-discussed instance of Himanta Biswa Sarma quitting the Congress party. Sonia Gandhi had given clearance to his taking over from Tarun Gogoi as the chief minister of Assam, who had proved to be unpopular with his legislators. Azad was supposed to visit Guwahati and convey Sonia Gandhi’s clearance of the plan and seek Gogoi’s resignation. But before he could do that, he was asked to meet Rahul Gandhi. In the meeting, Rahul Gandhi told him that Gogoi would not resign. This, despite knowing that Sonia Gandhi had given the green signal to install Sarma as the chief minister. When Azad said Sarma would leave Congress in such a situation, Rahul Gandhi said he was free to do so.

Now comes the really interesting part. When Azad informed Sonia Gandhi about Rahul’s stand, she was upset but accepted her son’s decision. Gogoi stayed and Sarma walked out later. Although Azad does not criticize Sonia Gandhi in as many words for meekly accepting her son’s decision which would lead to the decimation of the Congress party in Assam, even a causal reading of that episode in the book conveys the unsaid: that she failed to enforce her own decision—hardly a quality that a strong leader should have.

Let’s consider a second instance: that of N D Tiwari becoming the chief minister of Uttarakhand. Azad’s narration in the book of the case brings to the fore both the comical and the farcical aspects of the incident. The Congress party had registered a much-needed victory in the state elections, and among those who had campaigned hard was Harish Rawat. He had the support of a majority of the legislators. Azad discussed the matter of chief ministership with Sonia Gandhi, and it was decided that Rawat should assume the mantle.

But Sonia Gandhi, for some strange reason, suggested to Azad that he should consult the veteran N D Tiwari and take him on board. Tiwari’s contribution to the election campaigning had been next to nothing, and he was not even remotely considered for the chief ministership by anybody in the state. Azad met him and briefed him on the developments, informing him that Rawat would be assuming charge. Tiwari said nothing. Hours later, however, Sonia Gandhi spoke to Azad and told him that Tiwari had called her up and insisted on becoming the chief minister, and she had accepted his demand! In his book, while Azad refrains from questioning Sonia Gandhi’s capitulation, it should be obvious that he must have been displeased by her weak-kneed approach.

There is a third example. This is not from the book per se but from one of the recent interviews Azad gave after the book’s release. He spoke of a meeting that ten leaders of the so-called G-23 had with Sonia Gandhi, in the presence of Rahul Gandhi and Priyanka Vadra, and a few other Congress leaders. On her directions, Azad later presented a set of to-do’s in writing— short-term, medium-term, and long-term. But nothing came of them.

Was it her decision to ignore those suggestions or did Rahul Gandhi give the veto? Given that Azad says that Sonia Gandhi listened to party seniors and often implemented the ideas they offered, why then did she ignore those suggestions? It may have been under Rahul’s influence, but once again it does not speak highly of Sonia Gandhi’s leadership.

That Azad has avoided being directly negative about Sonia Gandhi, even when there was cause for it, is clear. But in his own subtle way, he has tried at times in the book to draw the line in showering unadulterated praise on her. One may recall that after the Congress and its allies scored a win in the 2009 Lok Sabha elections, there had been a scramble to give credit for the party’s return to power to Sonia Gandhi’s ‘able leadership.’ Azad writes in his book that the full credit for that victory goes to Manmohan Singh—for his effective governance in the first term and the firmness he displayed in going ahead with the civil nuclear deal with the US despite criticism from not rival parties but also from within the party and its allies.

In the 2009 election context, Azad also observes in the book that for the Congress party’s excellent showing in Andhra Pradesh, the party would not have got the numbers to stake claim to form the government at the Centre. Sonia Gandhi’s contribution to the party’s stupendous performance in Andhra Pradesh was marginal, if any at all—if one reads between the lines in what Azad writes.

Azad’s reluctance to unequivocally target Sonia Gandhi’s leadership is understandable; he was close to her husband, Rajiv Gandhi, a person for whom he has total admiration and respect. While on this subject, incidentally, Azad has also avoided saying anything negative about Maneka Gandhi, despite her fallout with Indira Gandhi—a leader for whom he has nothing but praise and adoration all through the book. Here again, Azad kept in mind his close association with Maneka’s husband, Sanjay Gandhi, who was both his friend and his leader.

While the book is full of arresting anecdotes and revelations, one gets the feeling that, had Azad’s gentlemanliness not come in the way, there would have been many more of the explosive stuff.

Note:

1. Text in Blue points to additional data on the topic.

2. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of PGurus.

PGurus is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel and stay updated with all the latest news and views

For all the latest updates, download PGurus App.

Any self respecting person will NOT stay with the Congress when RG got nominated as president of the party. The fact that Azad stayed that long speaks a lot about him, and those who are still sticking with Congress tells even more about them!