The first part of the this article can be accessed here. This is part 2.

HOW DELHI RESPONDED TO THE SOS CALL FROM MAHARAJA HARI SINGH

Brig Amar Cheema in his book The Crimson Chinar has given a detailed version of the episodes preceding Accession Day.

According to the excerpts, “News of the Pakistan sponsored Qabali invasion reached Delhi on 24 October via two channels. Generals Auchinleck and Lockhart were informed by the officiating C-in-C of the Pakistan Army, General Gracey, and by the evening, the second input came through Mr R L Batra, the Deputy Prime Minister of Kashmir, who had flown to Delhi with an urgent request from the Maharaja. His mission requesting for immediate help also conveyed the willingness of the Maharaja to accede to India to save his state from the ‘Marauders’ as he dubbed the Qabalis, who by then had already ravaged Uri and had the same state was feared for Baramulla.

The next day the Defence Cabinet Committee (DCC), chaired by Louis Mountbatten held their first meeting. Against strong opposition from the Service Chiefs and from Lord Mountbatten himself, it was decided to help Kashmir militarily. However, what could be adduced as delaying tactics, it was decided to send Mr Menon to Srinagar to make an ‘on the spot’ assessment. As a consequence, Menon and Batra flew to the valley the same afternoon.

Mr Attlee requested both Nehru and Liaqat to avoid precipitating the situation which could lead to a military confrontation.

Concurrent to these developments in Delhi, Sheikh Abdullah sent Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed and GM Sadiq to Pakistan to meet Mr Jinnah and/or Mr.Liaqat Ali Khan. This move of Sheikh Abdullah proved abortive as Jinnah sensing victory did not deem it prudent to meet the emissaries, now that success was within his reach. This enraged the Sheikh and he flew to Delhi and met Pundit Nehru. In fact, he was there when Batra reached Nehru’s house on 24 October. On the same day Pundit Nehru informed Prime Minister Attlee of the developments and that India was considering military intervention. Mr Attlee responded by requesting both Nehru and Liaqat to avoid precipitating the situation which could lead to a military confrontation.

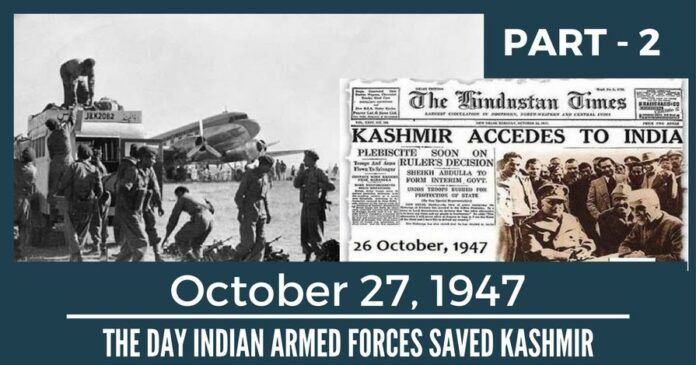

When Menon flew back the next morning, Mr Mahajan, the Prime Minister of Kashmir, also flew in with him and he carried the letter seeking accession to India. Thus, 26 October was the date when after a stormy DCC session, the decision was taken to send Indian troops to the rescue of the state. The situation had become so acrimonious, that the Indian Ministers were constrained to state that since the British officers opposed the operation, they could step down and it was Mountbatten’s intervention that saved the situation. However, after this ugly turn of events, he took upon himself to become the de facto military advisor for the impending Indian operation.

Another Military historian and former Governor Lieutenant General (Retd) S K Sinha in his book, Op Rescue: Military Operations in J & K, 1947-49 has brought out the circumstances when instructions were received at HQ Delhi and East Punjab (DEP) Command.

One term of reference was laid down at the outset; no British or Muslim officer who had opted for Pakistan could accompany the forces.

General Sinha, who was then a Major, recounts how they had been summoned to the Operations Room at 2200 hours on the evening of 26 October 1947, when the Army Commander, General Russell tasked them for the ‘rescue’ of Kashmir.

He instructed his officers to expeditiously dispatch one Battalion group by air to Srinagar using a combination of Air Force and civil aircraft and one Brigade group by road to Jammu; moves which were required to commence by first light the next day i.e. 27 October.

The Battalion for Srinagar was required to be built to a Brigade group before the onset of winters. One term of reference was laid down at the outset; no British or Muslim officer who had opted for Pakistan could accompany the forces. With one stroke, this reduced the availability of officers to lead the expeditionary force. The military imperatives for the task entrusted to Russell are analysed below:

Securing Srinagar Air Head

This was paramount as the air was the only means to build up forces in the time frame. It is pertinent to interject that in the absence of information, especially on the security of the airfield, it would have been militarily desirable to have provided a fighter-bomber escort and paratroopers with the first wave to secure the air head. Had the landing been opposed, India may not have been able to recapture the valley as the instructions to Colonel Rai were to land only if the airfield was un-held.

From Pakistan’s point of view, going by the timing of Op Gulmarg, it was expected that the airfield would be in the hands of the raiders by the 24/25 October. It was the delay in Baramulla that upset their time plan and provided the window to land forces.

Independent India’s First Expeditionary Military Deployment

The honour of the first unit going into combat on behalf of Independent India was bestowed on 1 SIKH, whose Commanding Officer (CO), Lieutenant Colonel Ranjit Rai had taken over the unit recently and fortuitously, the Battalion had been conducting internal security duties in Gurgaon. HQ 161 Infantry Brigade, commanded by Brigadier J C Katoch who had moved for internal security tasks from Ranchi was available as the formation for controlling operations in the valley; while the second formation selected for the Jammu sector was 50 Parachute (Para) Brigade under Brigadier Paranjape. It may be pertinent to point out that as a result of their internal security role, 1 SIKH was not carrying heavy weapons, which had to be hastily found for them.

“I must mention that his calmness was indeed inspiring. He showed no excitement or agitation and appeared, as always, supremely self-confident. “

It is to the credit of Rai and his men as well the staff of HQ DEP and the numerous airmen, both military and civil, who rose to the occasion and affected the airlift flawlessly. The personal impressions of General Sinha, as the Command HQ staff officer assisting Rai in the airlift of the man given this arduous task is worth recounting and is quoted both as a tribute and as an inspiration for military leadership. “I must mention that his calmness was indeed inspiring. He showed no excitement or agitation and appeared, as always, supremely self-confident. With my little experience of war, I am convinced that calmness and self-confidence during stress and strain are very important assets for a good leader. Self-confidence in a leader is contagious, it soon spreads among the led, and a self-confident fighting team is a battle-winning factor.”

An extraordinary airlift was hastily organised seemingly from nowhere and speaks volumes not only for the team and staff work between the Air Force and the Army but also with the Civil Aviation.

The command and control of the forces for the forces to operate in Kashmir remained awkward, to say the least. HQ DEP, which essentially was an ad-hoc HQ was organised to control the internal security situation and in no way was it geared up to oversee full-fledged operations in distant Kashmir. However, being located in Delhi, it was made responsible for collecting, transporting and arranging logistical support of the forces being sent to Kashmir; the operational control of the forces, however, rested directly with Army HQ. This arrangement continued till late and resulted in the war being remotely controlled from distant Delhi, with no intermediate HQ in between, and in the initial stages, 1 SIKH was directly reporting to Army HQ.

The Air Bridge and Build up in the Valley

With the Pakistan sponsored tribals virtually knocking on the gates of Srinagar, the only way to plant Indian boots on the ground was to provide an immediate air bridge to the valley. What followed was an extraordinary airlift hastily organised seemingly from nowhere and speaks volumes not only for the team and staff work between the Air Force and the Army but also with the Civil Aviation. With three Dakotas of the RIAF and six mustered from the civil, twenty-eight sorties were affected on 27 October itself.

By 6 November, approximately 3,500 troops along with their supplies and equipment had been airlifted to the valley. This was an unparalleled feat, especially in the context of the sub-continent.

The civil planes carried 15 fully kitted soldiers along with 225 kgs of supplies while the RIAF planes carried two additional men. Hence, it was only possible to accommodate the Tactical HQ of 1 SIKH, one Rifle Coy and one Composite Coy of the Artillery in the first lift. The first two flights took off as planned and commenced landing at 0830 hours. By 1000 hours, the force was on the ground and this information was relayed to the relief of Delhi and this momentous event marked the first military deployment for war by Independent India. By 6 November, approximately 3,500 troops along with their supplies and equipment had been airlifted to the valley. This was an unparalleled feat, especially in the context of the sub-continent.

Lord Mountbatten who had been proved wrong by the Indians was full of praise for the effort and he went on to write, “..in his war experience, he had never come across an airlift of this order being successfully undertaken with such slender resources, and at such short time.”General S K Sinha, who himself was involved with the airlift as a staff officer, was to call this effort a ‘miracle.’ The important lesson to take home from the airlift was the alacrity of response and unity of purpose which was displayed by the men ‘in’ and ‘out’ of uniform. Without this, as the late Air Commodore Jasjit Singh has pointed out, the valley and with it Kashmir, would have been lost.

Maqbool Sherwani, a gutsy lad of nineteen years intentionally misled the enemy and had delayed them at the cost of his life.

The timely demolition of the bridge was the first of the acts that saved the valley and the officer’s valour earned him eternal recognition as the ‘Saviour of Kashmir’ apart from the award of Independent India’s first gallantry award, a well-deserved MVC.

KASHMIRI HEROES

Kashmir produced its own heroes and the story of young Maqbool Sherwani is remembered till date. This gutsy lad of nineteen years intentionally misled the enemy and had delayed them at the cost of his life. Despite being publicly tortured, the fearless lad cried “victory to Hindu-Muslim unity” till he was finally shot dead by the raiders. The wanton lust of the Qabalis along with the heroism of Kashmiris like young Sherwani dashed the Pakistani dream of liberating Kashmir. The extraordinary courage of this ordinary Kashmiri galvanised the valley and it is to the credit of the Kashmiris, who regardless of their religion came out on the streets to express their solidarity and to provide support to the NC which quickly moved in with their volunteers to control the situation created by the collapse of the civil administration. The cry that went up throughout the valley was “Hamlaawar khabardar, ham kashmiri hai tayyar.

Note:

1. Text in Blue points to additional data on the topic.

2. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of PGurus.

- IAF convoy ambushed by foreign terrorists in Poonch - May 4, 2024

- Assembly polls in Jammu and Kashmir soon: Modi - April 12, 2024

- Campaign trail: Udhampur-Doda Lok Sabha seat - April 8, 2024