New Delhi

[dropcap color=”#008040″ boxed=”yes” boxed_radius=”8px” class=”” id=””]S[/dropcap]uch was the British hatred towards Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose that they wanted to hang him after the end of the World War II. The Netaji files which were declassified on Saturday reveal that a week after Netaji reportedly met with a plane crash at Taihaku in Taiwan on August 18, 1945, the British had no clue of the disaster and were engaged in taking decision on his fate.

The files also show that the British believed that after the end of the World War Netaji was somewhere in Russia…

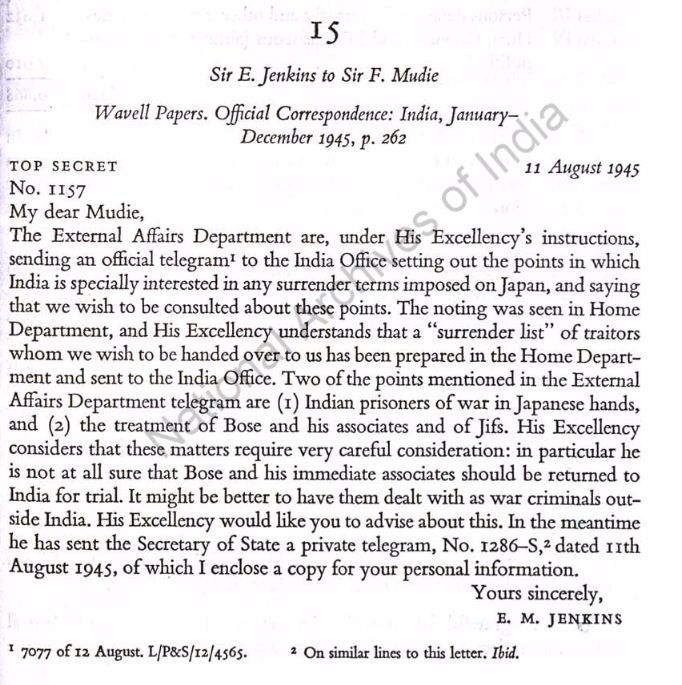

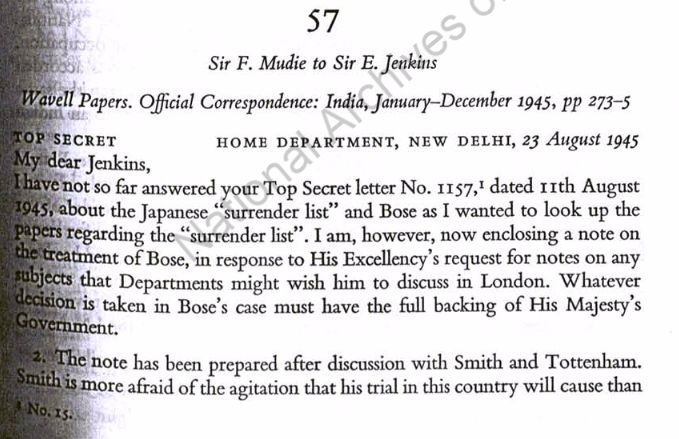

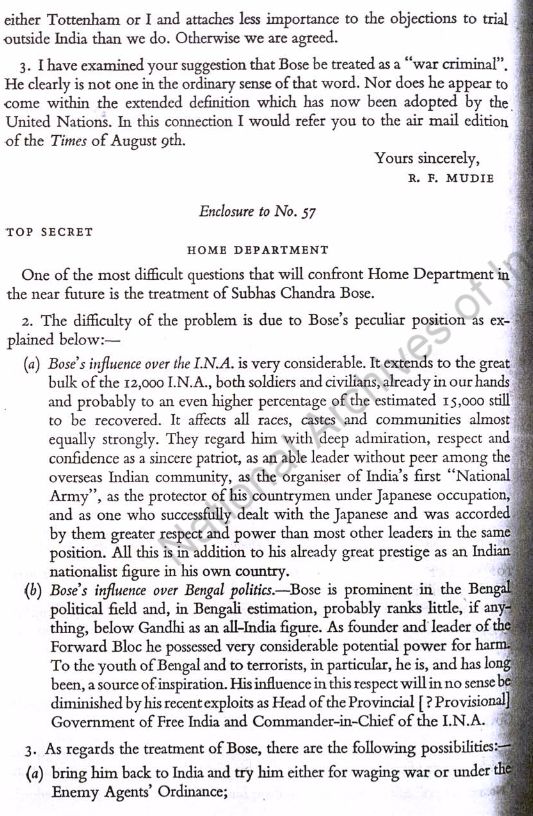

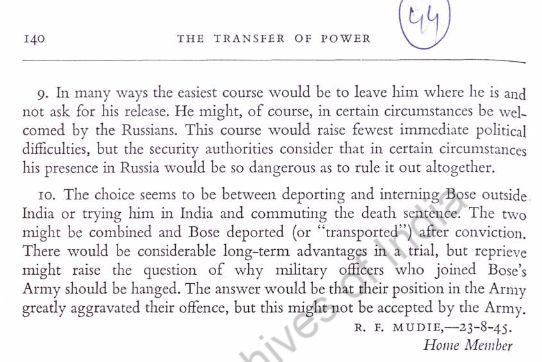

[dropcap color=”#008040″ boxed=”yes” boxed_radius=”8px” class=”” id=””]O[/dropcap]n August 23, 1945, five days after the reported plane crash at Taihaku, Sir R. F Mudie, Home Member, Clement Attlee Government’s India Office, wrote the following note to Home Secretary and the last Governor of Punjab, Sir EM Jenkins, who, on August 11, had sought Mudie’s views on what to do with Netaji.

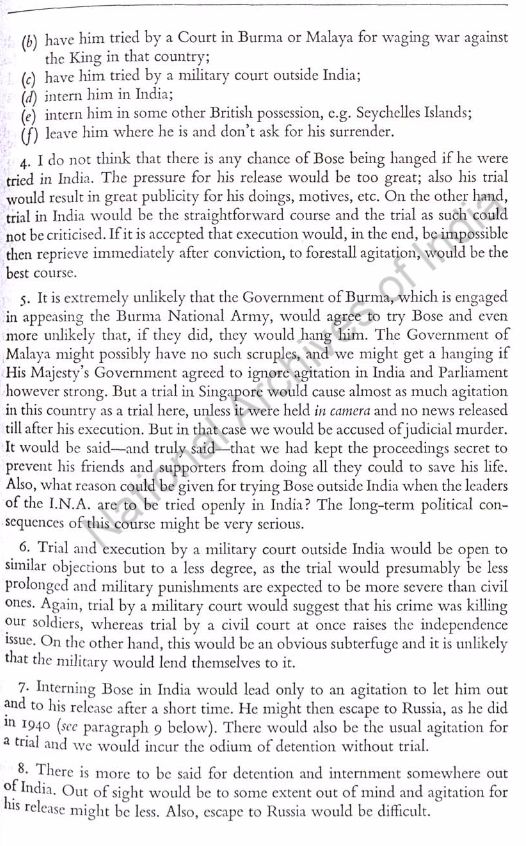

“It is extremely unlikely that the Government of Burma which is engaged in appeasing the Burmese National Army would agree to try and even more unlikely that, if they did, to hang him. The government of Malaya might not have any such scruples, and we might get a hanging if his Majesty’s Government agreed to ignore agitation in India and Parliament however strong. But a trial in Singapore would cause almost as much agitation in this country, as a trial here, unless it is held in camera and no news released till after his execution. But in that case we would be accused of judicial murder. It would be said–and truly said— that we had kept the proceedings secret to prevent his friends and supporters from doing all they could to save his life. Also what reason could be given for trying Bose outside India when the leaders of the INA are to be tried openly in India?. The long term political consequences of this course might be serious.”

[dropcap color=”#008040″ boxed=”yes” boxed_radius=”8px” class=”” id=””]T[/dropcap]he letter further says that, “In many ways the easiest course would be to leave him where he is and not ask for his release. He might, of course, in certain circumstance be welcomed by the Russians. This course could raise fewest immediate political difficulties…”

These were some of the 10 options Mudie placed before the British Government.

The British were not sure if Netaji could be treated as war criminal. When Jenkins suggested that Netaji be treated as a “war criminal”, Mudie said, “He (Bose) clearly is not one in the ordinary sense of the word” and “nor does he appear to come within the extended definition adopted by the UN”.

Mudie listed following other possibilities to deal with Bose:

-

Bring him back to India and try him either for waging war or under the Enemy Agents ordinance.

-

Have him tried by a court in Burma or Malaya for waging a war against the King in that country.

-

Have him tried by a military court outside India.

-

Intern him in India.

-

Intern him in some other British possession, e.g., Seychelles.

-

Leave him where he is and don’t ask for his surrender.

[dropcap color=”#008040″ boxed=”yes” boxed_radius=”8px” class=”” id=””]T[/dropcap]he note says that interning Bose in India would lead only to an agitation to let him out and to his release after a short time. “He might then escape to Russia ( as he did in 1940). There would also be the usual agitation for a trial and we would incur the odium of detention without trial.”

On the issue of detention and internment to somewhere out of India, the note says,” Out of sight would be to some extent out of mind and agitation for his release might be less. Also escape to Russia would be difficult.”

Mudie concluded , saying, “The choice seem to be between deporting and interning Bose outside India or try him in India and commuting the death sentence. The two might be combined and Bose deported ( or transported) after conviction. There would be considerable long-term advantages in a trial, but the reprove might raise the question of why military officer who joined Bose’s army should be hanged. The answer would be that their position in the army greatly aggravated their offence, but this might not be accepted by the army.”

[dropcap color=”#008040″ boxed=”yes” boxed_radius=”8px” class=”” id=””]T[/dropcap]his note is sufficient to show that the British were in a great awe of Bose and wanted to get rid of him at any cost, preferably by ensuing his hanging.

Reproduced below are the copies of the letters from Netaji’s files…

- The rise of Patanjali:An Indian yogi’s challenge to MNC giants - January 26, 2016

- Padmas – a blend of excellence, politics and ideology - January 25, 2016

- Scared of hispopularity, British wanted to hang Netaji - January 24, 2016

Bose was surely alive after the W II and the letters indicate that the allies wanted him to be hanged some how. Indian govt after independence did its best to undermine cause of Bose. it has to be blamed surely