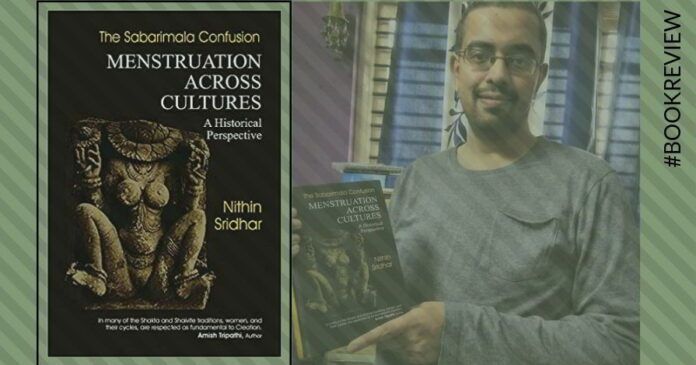

This book is a scholarly response to the toxic narrative by adharmics by examining menstruation practices across many cultures in order to educate and raise awareness.

The genesis of this book lies in the author’s series of articles on “Hindu Views on Menstruation” published in IndiaFacts.org in 2016 as a response to the then evolving Sabarimala situation.

Books such as these, catering to a regular audience, is the need of the hour. Because the success of Indic Renaissance rests on dharmics ability to reach the common man with a simple message.

The popular discourse on Sabarimala wrongly attributed women’s entry to gender inequality and negative notions of menstruation in Hindu culture. The adharmic media cabal in India launched propaganda citing oppression and discrimination of women in Hindu culture and belittled Hindu traditions. The knowledge gap that exists between the popular discourse on menstruation and public awareness on the cultural aspects of the same was exploited by the adharmic cabal. This book seeks to fill the knowledge gap on the Hindu notions of menstruation. It is, in fact, scholarly response to the toxic narrative by adharmics by examining menstruation practices across many cultures in order to educate and raise awareness.

The following traditions are covered as part of review and analysis:

- Dharmic: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain and Sikh traditions.

- Abrahamic: Christianity, Judaism and Islam.

- Ancient Western Civilization: Greece, Rome, Mesopotamia and Egypt

- Indigenous Communities: North, South and Central America, Africa, South East Asia, Australia and Europe are covered in a brief manner.

The author draws context, facts and references primarily from traditional texts in support of his analysis.

He covers notions of impurity, austerity, self-purification and sacredness in each of the traditions and rounds off each section with a comparative analysis (with Hindu tradition) to reinforce and highlight commonalities and differences.

The book begins with an analysis of Hindu notions of menstruation by pointing out the connection between the menstrual cycle and the lunar cycle and its references in various Hindu literature – Ayurveda, Jyotisha and Kamashastra. It is informed that Ayurveda recognizes synchronization between menstrual and lunar cycles as “best condition for women’s health and fertility”. The author subjectively interprets Indira’s karmic guilt that manifested into menstruation for women.

Nithin cites numerous references from within the Hindu literature on how menstruation is viewed vis-a-vis ashaucha (“ritual impurity”), austerity, self-purification, and as a sacred celebration.

On the notion of ashaucha, he explains how the yogic philosophy of Pancha-Koshas (the five layers of an individual – Annamaya kosha (physical), Pranamaya kosha (vital), Manomaya kosha (mental), Vigyanamaya kosha (intellect) and Anandamaya kosha (bliss)) differ from modern view of impurity which concerns only with the physical level.

He goes on to analyze austerity, self-purification and sacred celebration.

In fact, he cites numerous references to the sacred celebration at the onset of menstruation (called menarche) across India – among many communities in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Orissa, Karnataka, Bengal and Maharashtra. The celebration is called Manjal Neerattu Vizha in Tamil Nadu from where I come.

He points out to Tantric practices & certain sections in Upanishads that highlight the sacred treatment of menstruation. There are many temples across India that celebrates menstruation – his examples include Ambubachi festival in Kamakhya Temple in Assam, Raja in Odisha, Chengannur Mahadeva Kshetram in Kerala, and the Keddasa festival in Dakshina Kannada district of Karnataka.

He extends his analysis to Yoga and Ayurveda – the two knowledge systems, to explain why there are restrictions on menstruating women. He shares the results of a couple of scientific studies conducted on a few women by following the Ayurvedic practice of Rajaswala Paricharya. The results show how following the ayurvedic practice reduced common menstrual symptoms (pains, cramps, pimples etc) amongst the majority of the participants. I repeat, these are as a result of scientific studies.

The author cites these examples and references from a variety of dharmic literature to buttress the point that Hindu treatment of menstruation is positive. He concludes his analysis of Hindu notions of restrictions as being “therapeutic” as opposed to being “oppressive”.

He moves on to analyze other Dharmic traditions – Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism, which not surprisingly, share many notions of Hindu Dharma. Sikhism is the only dharmic tradition that does not construe menstruation as impure.

Next, he extends his analysis to Abrahamic traditions covering Judaism, Christianity and Islam in that order. He notes that the notion of impurity is fundamentally different between Hinduism and Abrahamic traditions. In Christianity and Islam, this is associated with the biblical concept of the Original Sin. This had sad repercussions for women in the Christian Society. The liberal notion of women’s rights is a reaction to the oppressive and inhuman treatment of women in Christian society in the middle ages. This liberal notion was wrongly applied in the Sabarimala context.

Nithin draws the reader’s attention to how western traditions of Greek, Rome, Egypt, Mesopotamia and many different indigenous communities around the world treat menstruation. It is quite surprising to note the similarities that exist on the notion of impurity and sacredness throughout the world.

Although not a great fan of Ashish Nandy, I am tempted to quote:

“Modern colonialism won its great victories not so much through its military and technological prowess as through its ability to create secular hierarchies incompatible with the traditional order” from his book The Intimate Enemy: Loss and Recovery of Self Under Colonialism.

In the emerging Indic Renaissance, this book is quite an attempt to contribute to the destruction of secular hierarchies built over 200+ years and help create a decolonized mind.

The author’s writing style is simple. Gladly, he does not succumb to the temptations of intellectual orgasm. Books such as these, catering to a regular audience, is the need of the hour. Because the success of Indic Renaissance rests on dharmics ability to reach the common man with a simple message.

I like to end the review with this beautiful quote by popular chef Jose Andres:

“The modernity of yesterday is the tradition of today, and the modernity of today will be tradition tomorrow”.

I request the milords of India’s Supreme Court to take note of it.

Note:

1. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of PGurus.

- US Elections 2020: The Democratic dissonance - June 28, 2020

- Book Review: How India Sees The World by Shyam Saran - June 6, 2019

- Book Review: Menstruation Across Cultures, a historical perspective by Nithin Sridhar - May 13, 2019

Good review. Starting from the origin and give a glimpse of how reasoning of customs can get drifted in the name of free society.