VK Krishna Menon was supremely witty, and his wit could cut through ice, is gleefully reported by the author toward the very end of the book. This biography has many commendable qualities.

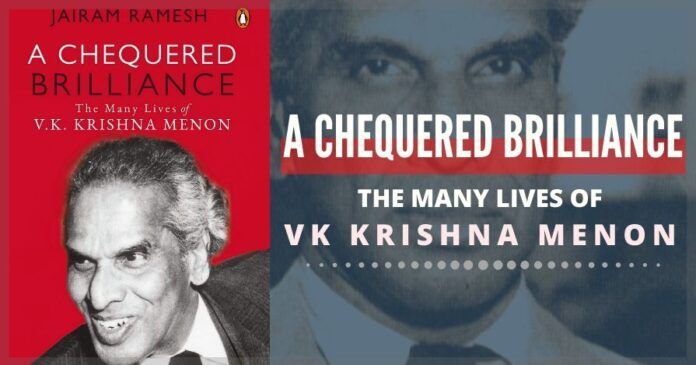

Jairam Ramesh’s biography of VK Krishna Menon, released recently, has many commendable qualities. One, it is based on fresh material from the archives. Two, it presents the protagonist’s complex personality — political and personal— in a holistic way. Three, it does not let the biases of the author (a Congress Member of Parliament) to intrude into the narrative. Four, it both celebrate Menon’s achievements and highlights his short-comings. Five, it allows readers unfettered freedom to arrive at their own conclusions. Above all, the book is a valuable addition to the literature on our eminent political leaders. Anything less than that would have been a disappointment to the reader who has laid his hands on this 700-plus page tome.

Despite Nehru’s regard and respect for him (which was clear in his letters), Menon on occasions plunged into despair and observed that he was perhaps not adequately understood by the man he had unqualified admiration for.

An indication of Jairam Ramesh’s resolve to present an account largely devoid of partial brush-strokes is evident in his introductory remarks to the main contents of the book: “I narrate a complex tale letting the written materials speak for themselves. Krishna Menon is an eminently fit subject for what has been called ‘psychohistory’… This is not a judgemental undertaking…” That may be so, and admirably, but it does nevertheless leave ample scope for the reader to judge both the author and the subject. One suspects Jairam Ramesh would not be displeased; after all, a book has little purpose if it does not trigger opinion.

The two pillars on which A Chequered Brilliance rests are the correspondences between Menon and a large number of important people in the UK, the US, elsewhere, and of course India; and, his unique relationship with Jawaharlal Nehru, which too is reflected in the letters that the two exchanged over the decades since they came into contact and a little before, as well as the then Prime Minister’s robust defence of his colleague in times of crisis. Taken together, they not only tell a good deal of Menon the man and politician but also the story of India in the run-up to independence and after (to the time Menon was active in politics and later, in social life). The author has deftly used these materials to construct Menon’s persona — a strange mix of self-confidence and self-pity, of dazzling intellect but also traces of arrogance. It says something of the man that he managed to achieve so much even while battling health issues throughout his life. Jairam Ramesh draws a picture that reflects Menon’s clarity of thought on the most complicated subjects, but which also represents some hallucinatory behaviour when Menon saw conspiracies where none existed. For instance, despite Nehru’s regard and respect for him (which was clear in his letters), Menon on occasions plunged into despair and observed that he was perhaps not adequately understood by the man he had unqualified admiration for.

Anybody who has had even a casual interest in India’s contemporary history would be aware of the two big reasons that made VK Krishna Menon a household name in this country and fetched him worldwide recognition. One is the marathon eight-hour-long speech he made in the United Nations in defence of India on the issue of Jammu & Kashmir. And the other is his tenure as Defence Minister during which the nation faced massive humiliation in a war with China. He emerged a hero toasted across the country in the first instance, and a villain in the second for having grossly mismanaged his portfolio, even politicising the Armed Forces. Jairam Ramesh has dealt with both cases in some detail, without either over-glorifying or underplaying. The author admits to Menon’s blunders, especially the manner in which he sought to undermine the authority of the Army chief and promote officers of his choice. Nehru did his best to shield Menon from the fallout of the defeat, writing to former President Rajendra Prasad after securing Menon’s resignation, that he did not think the “propaganda against him was at all justified”. Menon had promptly quit after being asked to do so, but Nehru kept him in the Cabinet as Minister for Defence Production — which Menon boasted of, much to the irritation of some senior party colleagues. Jairam Ramesh writes that Nehru adopted a curious path to accepting the resignation, writing to then-President S Radhakrishnan seeking his opinion. The author quotes Radhakrishnan’s biographer S Gopal, who wrote that “Nehru wished to leave the responsibility for the final decision to the President, with perhaps a subconscious hope for at a delay in, if not abandonment of, Menon’s departure”.

That said, the author refuses to fall in the conventional trap of laying every blame for the defeat at Menon’s doorstep. He points out that the then Union Finance Minister Morarji Desai had been uncooperative in making funds available for the needs of the defence forces. Jairam Ramesh also produces letters of appreciation from various people for the services Menon had rendered as Defence Minister, including from Navy chief Admiral Ramdas Katari. Following his resignation, Menon was to be associated with Nehru in various ways for the next year-and-half till Nehru’s death, and this often triggered speculation that he may make a comeback. A British official, clearly not an admirer of Menon’s, reported back to his superiors in London in the following words: “Mr Krishna Menon is, I regret to say, in excellent health and spirits… There are other indications that he is by no means out of action these days.”

Ramesh writes that it was a “bravura performance” and that it was the “first time in seven years that India’s case on Kashmir was made with passion, eloquence, historical facts and political realities”.

Riding on his UN dramatics, Menon was elected to Parliament with an imposing majority in 1957, “without much campaigning”, according to Jairam Ramesh. The author explains that this was “almost entirely on the strength of his performance at the UN”. Thus, just five years before he would leave the ministerial office in some disgrace, Menon had been toasted by Indians for his historic speech in the United Nations on Jammu & Kashmir. The UN was discussing a complaint lodged by Pakistan on the adoption of a Constitution for the then State, claiming that it had violated six resolutions of the world body passed during 1948-50. Menon first took the floor for “five hours and five minutes, and continued the next day for another two hours and thirty minutes”. Ramesh writes that it was a “bravura performance” and that it was the “first time in seven years that India’s case on Kashmir was made with passion, eloquence, historical facts and political realities”. Days later, Menen collapsed with fever, low blood pressure and sheer fatigue. He later informed a worried Nehru, “I am better now and will be able to function… unless there is a relapse which is not expected.”

But while his UN histrionics brought him national and international fame, it is not as if he had been a non-entity before. As Jairam Ramesh reveals in detail in the earlier chapters of the book, Menon had worked ceaselessly for India’s cause while based in the UK, first as a student and later as an activist for the India League, which lobbied for India’s interests including freedom from colonial rule. Indeed, it is this part of the book that brings to the reader the true mettle in Menon, and it is this role of his which brought him to Nehru’s notice. Here, the patronage he received from Annie Besant fetched him the early recognitions. This was well before Nehru came into his life.

The Menon was supremely witty, and his wit could cut through ice, is gleefully reported by the author toward the very end of the book. Once, responding to criticism by a British delegate at the UN in 1957 of the use of English language in his speech, Menon said: “I can understand your difficulty in understanding what I have said; you picked your English on the streets of London, I devoted several years of my life to learn it with the care and respect it deserves.”

It can be said of Jairam Ramesh too, that he wrote this biography with the care and respect the subject deserved.

Note:

1. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of PGurus.

They were lovers. period. they co-habited for thirty years. They belonged to the homosexual underground at university, along with Mountbatten. Mountbatten was accused of molesting young ratings in the navy. His

wife Sylvia claimed she needed a new female lover every month. Nehru wore saris at dorm parties.

Is there any mention of the infamous jeep scandal that is credited to Mr. Menon. Nevertheless, it seems a good book to be read for its balanced presentation as reviewed.