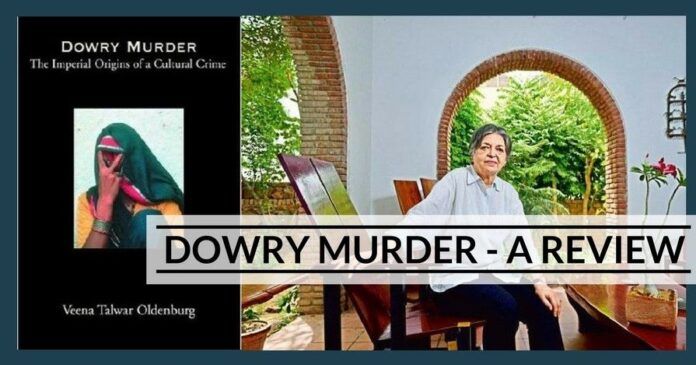

“The undue emphasis on dowry often serves as a smokescreen that obscures other exacerbating causes for marital violence against women”

Blame it on Hindu Culture

The book is an exposition of how the introduction of colonial policies in Punjab, turned a respected institution such as Dowry into a fiendish practice in the 20th century. The colonial administrators blamed dowry and wedding expenses for female infanticide, linked the practice to Hindu upper caste customs to justify their civilizing mission.

The author writes:

“To ensure against the political dangers of intrusive social reforms, the East India Company sought native participation in framing the crime as a cultural product.”

This model was first tried and tested successfully with the ban of Sati in 1829.

It is in this context one has to investigate and evaluate “dowry murder” or “bride burning”. The book does that pretty well. It dispels the cultural origins of the crime using prodigious research and proves the fallacy of colonial reasoning about dowry.

From her initial investigations its amply clear:

“The colonial finger pointed at Hindu culture, whereas present-day Indian activists and media blamed Westernization, which increased materialism, greed, and desire for consumer goods”

Female infanticide

She sets out on a marathon 15-year effort to uncover the root cause. Quoting her :

“I began to skim through annual compilations of administrative reports in Punjab to see if, perhaps, a hundred years ago the custom of dowry had better press. And there it was, as a cause of the murder of females. But instead of the murder of brides, it was categorically indicted as the cause of female infanticide.”

The investigation led to a startling discovery of the practice amongst lower caste Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims, who did not indulge in dowry practices!

Thus, female infanticide came under the ambit of her investigation.

The administrators focused on limiting wedding expenses to solve female infanticide.

There are numerous references to the works of modern anthropologists and scholars regarding dowry and property rights. While contemporary discourse delves into the vicious nature of dowry, the historical research had not disinterred any facts or evidence of violence in the pre-colonial period.

Author proceeds to unravel the mystery and in the process disentangles many “political, social, economic and cultural” facets at play.

Blame it on Caste

Examination of reports written by R. Montgomery, the Judicial Commissioner of Punjab (Minute on Infanticide, 1853) and Maj. R Edwardes, Deputy commissioner of Jalandhar, lays the blame squarely on upper caste despite evidence to the contrary.

The author narrates the story of Dharam Chand Bedi – grandson of Guru Nanak (founder of Sikhism) to whose times Edwardes traces the practice of female Infanticide. This was ONE family and their descendants over 300 years, since Akbar’s time.

“The Bedi’s story represents for Edwardes the end of a quest; he now has the irrefutable reason for the killing of female infants from a caste elder and it is unmistakably rooted in caste pride.”

What this did was to attribute the brutality to the grandson of Guru Nanak!

In many instances, survey statistics and findings were ignored to fit the colonial persuasion on Hindu culture. None of the 40 or so district magistrates in Punjab were able to explain the practice in lower caste Hindu communities or by communities (Hindus AND ***Muslims*** included) that do not pay dowries for daughters.

Administrators simply ignored those findings, dismissed them as mistakes as per their own admission and created atrocity literature.

This was in the early 1850s.

Fix Wedding Expenses to prevent female infanticide

It is clear from reports that the administrators focused on limiting wedding expenses to solve female infanticide. Many agreements to this effect were signed by chiefs of all castes & tribes, rajas, and maharajas, in a meeting in Amritsar in 1853.

What these agreements did was to limit various categories of wedding expenses besides eliminating goodwill gratuities (which proved counter-productive) to barbers, musicians and other village functionaries on festivals and special occasions.

A key observation by the author:

“The underlying conviction in these various agreements seems to be that the enforced reductions in expenditure should impinge not on the rights of the daughter but on the gifts given to the bridegroom and the kin.”

This is problematic because “identical or larger amounts of money were spent on the weddings of sons.”

Besides, wedding expenses were never considered to be a burden. The practice of preparing for a daughter’s wedding and marriage begins from her birth literally. The gifts are built up over a period of 15 to 20 years, contributed by family members.

This “made events such as a daughter’s wedding a shared responsibility and far less burden that the British believed it to be”.

Why then kill female infants? The question still lingers on.

Dowry – Stunning reversal between 1867 and 1916!

There were no strictures on dowry and no clauses added to any of the agreements signed in the 1850s.

The author asks:

“Dowries might have already cost many times more than all other wedding expenses put together. Why then, in 1853 or later, did the British officials not insist that dowries be regulated as much as wedding expenses itself?”

In April 1867, in response to an essay competition on female infanticide, Pundit Motilal Kathju, Assistant Commissioner of the Punjab Secretariat in Lahore:

“dowries, a traditional safety net for women, now served the interests of the husbands family to purchase more land, pay revenue in a bad year”

“systematically refutes the idea that pride of race and the heavy expense attending the marriage of daughters are the cause of the crime”.

She adds from Kathju’s essay:

“Among Punjabi upper castes, particularly Brahmins and Khatris, the dowry was the preferred and decidedly honorable practice”.

She categorically states:

“The dowry demands complained about in the 1960s were non-existent in 1867. There is no evidence in this period that the groom’s family either bargained for a dowry or made dowry demands, it is emphatically seen as a matter of honor for the groom’s side to accept what is given as a dowry to the bride.”

Fast forward to 1916.

Upon reviewing Bolster’s report (1916) a stunning change was observed in the practice of Dowry. In 1916, British administration revised the 1868 Customary Laws of Lahore District. Key revision relevant to this context include:

“the articles that form the dowry are gathered together and shown to the marriage party as well as to the girls’ brotherhood. The boy is then again called inside the house of the bride’s father and the dowry is gifted to him”

What a reversal in 50 years!

Preference for Sons irrespective of religion and caste

Continuing her investigation, the author undertakes several trips to Gurgaon district between 1989 and 1997. She finds out:

“Killing the child prevented lactation and cleared the way for the mother to become pregnant again, possibly to produce a son. When a newborn emerged from the womb and its genitals became visible, its fate was sealed; a penis saved the infant. This preference for sons subsumed all castes, tribes, and religions in the colonial period.”

She adds:

“The landowners were entirely dependent on family labor and this situation reinforced a very strong desire for male progeny”

Referencing Prem Chowdhry (1994):

“He has keenly analyzed the Jat peasants’ preference for males in the colonial period when their military and agriculturalist skills were in high demand”.

References to the works of Monica Das Gupta (1987), Peter Oldenburg (1992) and Peter Meyer (1999) explain how families

“controlled the number and sex of children so that the goals and interests of the family and the state are met”.

What are these goals and interests?

#1 Ryotwari System, fixed land revenue payments & male property ownership!

Introduction of the ryotwari system by the colonial administrators had a debilitating effect on landowners and created a debt trap. This exposed them to the risk of losing their land to money lenders.

“Land was declared a marketable commodity capable of private and determinate ownership so that a fixed and settled land revenue in cash could be recovered in two annual installments on two fixed dates”.

Britishers made *** three specific changes *** from pre-colonial times:

- Land revenue payments were changed to fixed cycles, from elastic. No flexibility was shown to adjust to seasonal influence.

- During bad times such as famine or drought which affected harvest, there was no remission. This caused landowners to mortgage land at a high-interest rate to pay land revenues.

- Modified property rights to give male members the titular ownership of land, so that “they could be taken to court or sent to jail” if they defaulted on revenue payments.

Fact-finding missions and surveys in the 1890s highlighted peasant indebtedness due to inflexible colonial revenue policies. However, the Britishers turned a blind eye to the facts, instead continued to blame dowry and wedding expenses!

In these situations:

“dowries, a traditional safety net for women, now served the interests of the husbands family to purchase more land, pay revenue in a bad year or bail themselves out of the hands of loan sharks”

#2 Codification, Legalization & Modification of informal customary practices

“Hand in hand with the recording of property titles and fixed revenue assessments went the compilation and reduction of a universe of customs into a tightly constructed code of customary law that altered the grammar of social relations”

The preference for sons deepened, “gender targeting”, was achieved through female infanticide.

In the process of codification and emendation, pre-colonial terminologies were given a new meaning in colonial terms. “Feudal” or “Village” became “Tribal”, the concept of “family name” and “given name” was introduced. The “family name” took on a caste identity.

This created a patriarchal society that introduced caste distinctions, modified gender relations & severely crippled women’s rights and power.

During the pre-colonial times:

“Men tilled the soil and defended it against local and external enemies. Men defended the rights of their family and their wives; widows and unmarried daughters shared in the heaps of grain and other produce it yielded”

Inheritance rights were changed too as a result of codification:

“Sons would inherit and be in charge, and their widowed mothers would be their dependents-at-will; women who had no sons would have no rights and would become dependent on the charity of their stepsons or the husband’s other agnatic kin”

#3 Job opportunities for Punjabi males in the military

East India Company escaped the first war of Indian independence in 1857 by skin of their teeth, and “reorganized into Britains Indian Army with vastly improved conditions of service”. British preferred to recruit Punjabi males into the military. This created job opportunities for males and increased financial security with attractive remuneration and benefits.

During “hard times created by the revenue policies that generated money to pay for them, a military career brought the peasant family the security that had been compromised by making its lien on land so tenuous”

The Result of it all

Colonial policies engineered a masculine economy.

The preference for sons deepened, “gender targeting”, in her own words, was achieved through female infanticide as a direct result of colonial policies. The negative effect of land revenue assessments coupled with greed and increase in material interests converted dowry from being a voluntary safety net into a mandatory or expected custom to ensure security.

What was once a relationship based society was converted to a contract based society by applying capitalistic ideas (individual land rights), importing British prejudices (crippling women’s rights) and advancing colonial motives (discrediting Hindu culture to justify civilizing mission).

Contemporary Times

The author turns to studying and analyzing historic cases of violence against women (several hundred) while undertaking research at an NGO, Saheli in New Delhi in the 80s and 90s.

Dowry deaths were found to be true only in very few cases. Interestingly, it was found to be spread across Hindu upper caste, lower caste and Muslim communities thus debunking colonial theories. The study also revealed that dowry was not always the ONLY reason for dowry deaths. Case investigation, interviews and analysis revealed that dowry became a victim of social circumstances and legal convenience.

She writes:

“The undue emphasis on dowry often serves as a smokescreen that obscures other exacerbating causes for marital violence against women”

The author wraps up the book with an epilogue that is quite revealing. The folly of pointing a finger at Hindu culture is evident.

Note:

1. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of PGurus.

- US Elections 2020: The Democratic dissonance - June 28, 2020

- Book Review: How India Sees The World by Shyam Saran - June 6, 2019

- Book Review: Menstruation Across Cultures, a historical perspective by Nithin Sridhar - May 13, 2019

Thank you Ma’am, to publish Real Story of Dowry… !!

Thank you for the clear indication of the sequence of events/factors that has led to dowry systems’ misuse from its original proper use.

Prof Veena Talwar studied the statistics of two crimes:

(1) In New York, some husbands kill their wives in order to collect life insurance payout

(2) In New Delhi, some husbands kill their wives because the dowry was not to their expectations

Prof Talwar found that the statistics of the two crimes are comparable. Nevertheless the two crimes are treated in a different way.

Crime # 1 is treated as a law and order problem, but not as a problem of Christianity, Judaism, atheism. Being a law and order problem, it is not put under the heading of a human rights problem. Therefore human rights agencies will not issue statements on Crime # 1.

Crime # 2 is treated as a problem of the Indian traditions, not as a law and order problem. Being a problem of the Indian traditions, it is put under the heading of a human rights problem. Therefore human rights agencies can issue statements on Crime # 2.

Great ! The Book n review !

Real Intelligent work !