J&K HC gave as many as 22 reasons in support of the historic judgement on Darbar Move

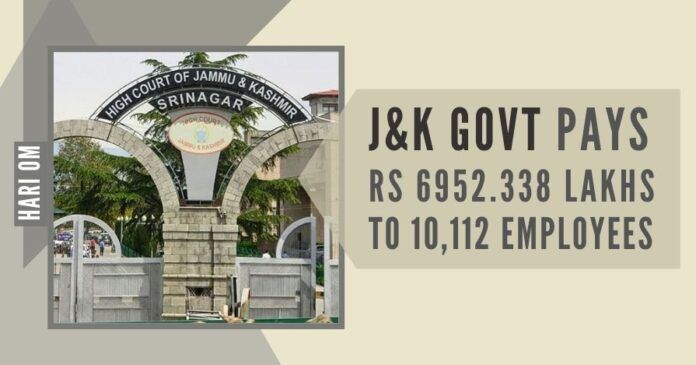

On May 5, 2020, Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) High Court bench consisting of Chief Justice Gita Mittal and Justice Rajnesh Oswal delivered a 93-page landmark judgement on the 148-year-old practice of Darbar Move in J&K (WP (C) PIL No. 4/2020 and WP(C) PIL No. 5/2020). The judgement asked the Union Home Ministry to review this archaic practice, saying that it was undesirable as well as not in the interest of the people of Jammu province, Kashmir Valley, and the nation as a whole. It gave as many as 22 reasons in support of the historic judgement. It, among other things, said that 10,112 employees move from Jammu to Srinagar in April and return to Jammu in October every year; that they do not work for 6 weeks every year; and that the salary of Move employees for six weeks for which no work is done in the Secretariat comes to Rs. 6952.338 lakhs. “For the year 2019, the disclosed expenditure on the Darbar Moves was to the tune of Rs. 19858.4298 lakhs. “If calculated for the 73 years period since independence on this basis, the total expenditure comes to Rs. 1449665.3754 lakhs,” the judgement said. In fact, the judgement very candidly asked: “Can any Government afford the annual expenditure of at least 200 crores (as disclosed and many more crores of rupees of undisclosed costs) to sustain and perpetuate an arrangement of bi-annual shifting of its capital two times a year, which originated in 1972?”

J&K State came into being after the Treaty of Amritsar in March 1846. The Treaty didn’t provide for interference in the internal administration of the state.

The judgement also said: “Apart from free accommodation, food of the employees is also highly subsidized and the burden foisted on the government. Only a monthly token amount of Rs. 400/- from non-gazetted and Rs 1,000/- from gazetted employees is charged for food.” Besides, it said: “Darbar move endangers safety and security of government records, many irreplaceable, priceless and even very sensitive nature, imperiling the security of the region as well as national security.” But more than that, it also said that “The practice of Darbar move impedes governance for six weeks every year to the huge detriment of public interest;” that the “Darbar Move doesn’t contribute to the economic growth of J&K;” that the practice “doesn’t contribute to emotional integration;” that the practice “denies justice to the people;” that it “leads to repeated adjournments;” and that “decentralization of powers between regions (Jammu province and Kashmir Valley) is a basic issue.” “Both the Jammu as well as the Srinagar regions equally require administration and governance around the year without interruption. It is unfair and opposed to the public interest to deprive either region completely of access to government machinery for six months at a time,” the judgement said.

As for the origin of the practice of Darbar Move, it said: It “originated in 1872 from the discomfort of the then ruler (Maharaja Ranbir Singh) of J&K with the harshness of the winter in Kashmir.” At the same time, the High Court admitted that no record was available on the origin of the Darbar Move. It also gave us to understand that the Darbar was shifted from Srinagar to Jammu in 1872. The judgement also asserted that “the Darbar Move was not implemented because of any traditional, social or political reasons.”

However, a peep into the history of J&K clearly suggests two things. One was that Jammu was the permanent capital of J&K and Darbar was moved from Jammu to Srinagar in 1872, and not from Srinagar to Jammu. The second was that the decision to shift the Darbar from Jammu to Srinagar in April for 6 months and from Srinagar to Jammu in October for six months every year was essentially political. It had nothing to do with the harshness of summer in Jammu and the harshness of winter in Kashmir.

It would be only desirable to reflect on the period between March 1846 and 1872 to put things in perspective and clear all the cobwebs of confusion. J&K State came into being after the Treaty of Amritsar in March 1846. The Treaty didn’t provide for interference in the internal administration of the state. But what happened after 1846 was intriguing. Instead of respecting the terms of the Treaty, the Imperialist British authorities started interfering with the day-to-day administration. It is quite evident from the records that the Dogra rulers were never allowed to rule independently. At each new succession, the policy of the British Indian Government was to weaken the new ruler and at each intended step of progress obstacles were placed in the way of the rulers. The British Indian Government, in ways more than one, tried to humiliate the rulers and to lower their position in the eyes of their people. They highlighted administrative lapses affecting the Kashmiri population, mostly the Muslims. This was perhaps because after handing over Kashmir to Maharaja Gulab Singh of Jammu (1846-1857), the British realized the unique importance of the Northern Frontier which lay between Russia and Afghanistan. By making things worse for the Dogra rulers, they wanted to secure a strong foothold in the state.

Between 1852 and 1877, the British got appointed a Commercial Agent at Leh in 1857, the year Ranbir Singh took over as the ruler of the State of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh State.

It was to achieve this objective that they started interference in the affairs of the State. They had already done the same in other princely states. This is evident from a letter in which Lord Harding, Governor-General of India (1844-48), wrote to Maharaja Gulab Singh in 1846 immediately after signing the Treaty of Amritsar under which Kashmir was added to the mighty Dogra Empire. In the letter, Harding stated that the “nature of his (Gulab Singh’s) administration had raised misgivings in the minds of the British” and claimed “the right on the part of the East India Company to interfere.” It is well to remember that they claimed the right to interfere with the state administration, not with a view chiefly to better the lot or condition of the people, but with the specific object of extending their influence along the Kashmir frontier for geopolitical and economic gains. This they wanted to achieve through the appointment of a Resident Officer. Maharaja Gulab Singh resisted and rejected the proposal. The matter was again raised in 1851 on the pretext of looking into the conduct of European nationals visiting the state, especially Kashmir Valley. The British policy bore fruit in 1852 when an Officer-On-Special Duty was appointed in Kashmir. This officer had no political authority. He was simply to supervise the conduct of European visitors to Kashmir.

Apparently, the appointment of an Officer-On-Special Duty was not of much significance. But taking into consideration the real motives of the British Government, this event was a very important one since it meant the recognition of the right of the foreign government to post their officers in the state. Moreover, what the Officer-On-Special Duty did was quite contrary to what was desired of him. He started finding faults with the state administration.

In the beginning, the incidence of interference was small and “ostensibly on behalf of the subjects of the state.” Subsequently, failing to achieve their political aim, the British adopted a rather hard attitude. Consequently, interference became almost a routine matter and the British government succeeded in achieving more and more political and economic concessions in the state.

Between 1852 and 1877, the British got appointed a Commercial Agent at Leh in 1857, the year Ranbir Singh took over as the ruler of the State of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh State. It was followed by the appointment of a British Joint Commissioner at the same place. In 1870, that year Dr. Henry Cayley, the first British Joint Commissioner, surveyed the trade routes through the Maharaja’s territories from the British Frontier of Lahul (now in Himachal Pradesh) to the territories of the ruler of Yarkand, including the route via the Chang Chenmoo Valley. This appointment proved highly beneficial to the British Government as it meant an opportunity to survey the Eastern portion of the territories of the Maharaja of J&K and to lower his position in the eyes of the people. Besides, the sphere of activities of the British Joint Commissioner was at par with the Wazir-e-Wazarat of Ladakh. One was an agent to the British Government and the other was of the Maharaja. Both the officers enjoyed co-equal powers which obviously meant harassment and inconvenience to the local population of Ladakh.

Prior to 1872, no European visitor to Kashmir was allowed thereafter on October 15th without the specific permission of the Maharaja. This restriction was removed by Lord North Brook, the Viceroy of India (1872-76) in spite of the opposition of the Maharaja. The fundamental objectives of the British Government had three reasons:

- To “obtain trustworthy information regarding developments beyond the border”. The

- To gain influence among the neighbouring tribes in Gilgit, Baltistan, Chitral, Hunza, Yasin, Iskoman, and so on.

- To force Maharaja Ranbir Singh (1857-1885) to help them construct military roads leading to the strategic Northern Frontier.

The fourth reason was instigated disgruntled Kashmiri Muslim leadership against the Dogra Maharaja. These were the fundamental factors which made Maharaja Ranbir Singh start bi-annual Darbar Move practice. His objective was to defeat the Conspirators in the British Government and in Kashmir, opposed to the Dogra rule.

It is hoped that Home Minister Amit Shah will look at all these facts in the fact, abandon the practice of Darbar Move and restore Jammu to her pristine glory by making it a permanent capital of the UT.

Note:

1. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of PGurus.

- ‘Kashmir My core constituency’: Revisiting July 12, 2003 to understand politics, Omar Abdullah-style - March 15, 2024

- Total deviation from traditional approach: Seven takeaways from PM Modi’s March 7 Srinagar visit - March 9, 2024

- Status of political parties: Why is further J&K reorganization imperative? - March 1, 2024

Peter bro, because there is no work and money is coming to their home.. They take up terrorism.. Other states people don’t take up terrorism..

We pay billions to our politicians and GOvt employees who not only do nothing, but harass and cause more trouble for the public. So let’s not start demonizing J&K or WB or any other states that the BJP does not like