Among the pet subjects the Congress has used to target Prime Minister Narendra Modi is his Government’s decision on demonetisation

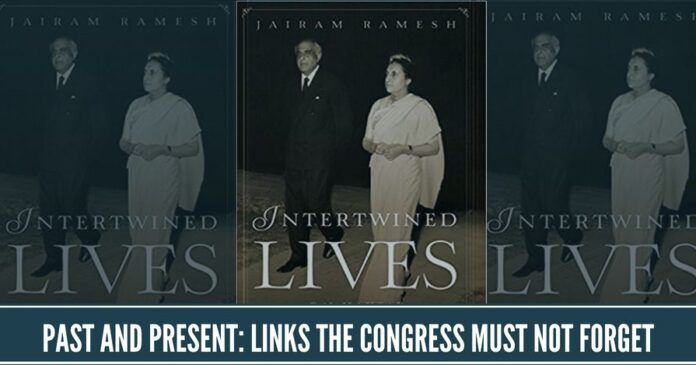

Senior Congress leader Jairam Ramesh’s book, Intertwined Lives: PN Haksar and Indira Gandhi, is an important contribution to the literature on independent India’s political developments. Ramesh gives us insights into a number of monumental decisions that Indira Gandhi took. A couple of these can be reproduced here simply because they can be placed alongside the ones the Modi Government has taken over the last four years and that which have drawn the Congress’s ire.

There had been a spate of critical pronouncements following Prime Minister Modi’s enormously successful visit to Israel.

Among the pet subjects the Congress has used to target Prime Minister Narendra Modi is his Government’s decision on demonetisation. The main opposition party said the Government’s move was bad and populist, that it was taken in a hurry without adequate preparation, and that it was implemented shoddily. Let’s see what Jairam Ramesh has to say about a similarly major and disruptive decision by the Indira Gandhi regime — that of bank nationalisation. He writes that even ten days before the nationalisation happened on July 19, 1969, the decision had been far from taken. He says that Indira Gandhi’s confidant and secretary, PN Haksar, was “thinking and talking in terms of ‘social control’ of banks”, and not a full-scale nationalisation.

But then things happened. A group within the Congress opposed to the Prime Minister propped N Sanjiva Reddy’s name as the President of India following Zakir Husain’s death. This was not, Ramesh writes, “to Indira Gandhi’s liking”. On the surface, though, she endorsed the candidature. Meanwhile, acting President VV Giri too filed his nomination. Ramesh notes, “It is improbable that he would be done it without Indira Gandhi’s knowledge…” The Prime Minister considered the camp’s move as an assault on her authority. Given that Morarji Desai was considered part of that lobby, she quickly divested him of the Finance portfolio. This was one way of demonstrating that she had control. The second was to announce the nationalisation, something she had been until then cautious about. Ramesh writes, “My guess is that between July 12 and 15, 1969, Haksar and Indira Gandhi must have confabulated and decided to shed their caution…”

Three objective inferences can be drawn from Ramesh’s account. One, the nationalisation happened abruptly. Two, it was hastened not by any economic consideration but by political developments. And three, only a close set of officers, including a Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, was in the know, given the sensitive nature of the decision. Given all this, it’s amusing that the Congress should be going on and on about the secretiveness and the alleged political oneupmanship regarding the recent demonetisation.

There had been a spate of critical pronouncements following Prime Minister Modi’s enormously successful visit to Israel. The Congress wondered whether it meant a reversal of India’s long-standing West Asia policy on the rights of the Palestinian people, and on the Arab world in general. The Congress’s Leftist friends were even more vocal in their condemnation. Jairam Ramesh narrates an incident which happened within a month of Haksar’s joining the Prime Minister’s Secretariat. The 1967 conflict in West Asia had erupted and Parliament was demanding answers on India’s position. Israel had been pitted in a war with its neighbouring rivals. The Bharatiya Jana Sangh had openly backed Israel, saying that the Arab world had never stood by India in its confrontations with Pakistan. Haksar prepared a note which the Prime Minister read in Parliament. Among other things, Indira Gandhi said that “Israel has escalated the situation into an armed conflict, which has now assumed the proportions of a full-scale war…”

The incumbent Government is often accused of being anti-Muslim vis-à-vis its West Asia policy

This was a clear denouncement of Israel, the ‘aggressor’. And yet, Ramesh writes, Haksar was to only four years later (with Israel still being considered the aggressor), through one of his London contacts, “explore supply of arms from Israel to India during its own war with Pakistan in 1971”. It is difficult to believe that Haksar had taken the initiative without the Prime Minister knowing. This was hypocrisy at its brazen worst, unlike in the present where the Modi Government has made no bones about India’s friendship with Israel — without hurting its ties with either Palestine or the rest of the Islamic world.

There is another aspect to this issue, which has a current context. The incumbent Government is often accused of being anti-Muslim vis-à-vis its West Asia policy. Haksar was, back in 1967, apprehensive about the religious colour being given to the matter. In a note, he sent to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi — which Ramesh produces in his book —

Haksar wrote about a meeting of the All India Palestine Conference, “I felt, however, a little troubled in seeing the Palestine question being cast exclusively in a religious framework. Even the question of Jerusalem is being viewed from the point of view of Islam… It is a pity that the organisers of the conference did not think of having a larger framework… The mobilisation of support for Arabs is not merely a question of mobilisation of support for Muslims…”

Hopefully, this message offered fifty years ago, will at least today percolate down to the leaders of the Congress and other like-minded ones.

Note:

1. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of PGurus.

Dear Sir,

Your last para says an important matter.

But who in the present “supposed to be” Congress, has got any analytical n realistic thought process.!